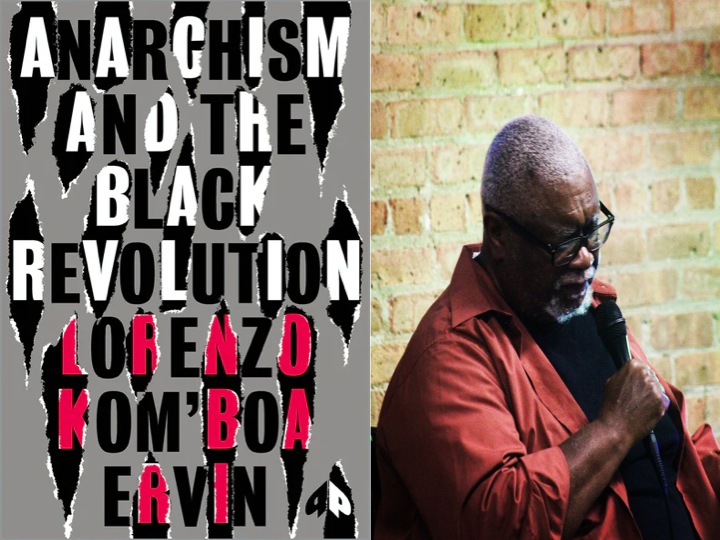

Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin’s “Anarchism and the Black Revolution” [Black Agenda Report]

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin. Ervin is an American writer, activist and black anarchist. He is a former member of SNCC, the Black Panther Party and Concerned Citizens for Justice. His book is Anarchism and the Black Revolution: The Definitive Edition .

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin: My name is Lorenzo Ervin, and I am a native of Chattanooga, Tenn. I came up during the 1950’s and 1960’s, during the fight against racial segregation in the South. I became an activist in my early years for civil rights and Black power.

I have been an Anarchist for over fifty years, primarily placing emphasis on class struggle, anti-racism, radical political education, and community organizing among peoples of color. Anarchism generally is a radical political, social and activist ideology for non-statist methods of social change. Rather than placing its primacy on the control of society to leaders, authoritarian political parties, or coercive methods of struggle, Anarchism is socialism from below, without the necessity of state apparatus. It is a broad based theory, and I have never claimed to capture all of its essential history, ideologies, or political formations. My approach is based on Libertarian Socialism, which has been in contention as a non-statist form of socialism since the First International Workingmen’s Association in the 1860’s.

Not familiar to many academics or Left activists, Libertarian Socialism is not totally based on Anarchist theory alone, there were historically unorthodox libertarian Marxist tendencies as well. This is an anti-authoritsrian, anti-state, and ideological form which is in opposition to electoral reformism, wage slavery in the workplace; and in favor of worker control of the economy, with overall decentralized control of society. It is the most radical wing of Anarchism, based on the grassroots.

I wrote Anarchism and the Black Revolution in 1979, while I was a political prisoner at the infamous United States Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. I was fighting for my life and for my sanity inside a solitary confinement unit which used forced druggings, beatings by guards, and psychic torture to “break men’s minds.” But I superseded the physical circumstances I found myself in, to break new ground ideologically.

I had been in prison for ten years and was already an Anarchist, totally opposed to the state and capitalism. I had long since come to the conclusion that it was the state itself that was the greatest purveyor of violence. It was certainly the racist authority responsible for the oppression of Black people, not just individual whites, nor prejudiced features of a white society. The white government did the bidding of a capitalist state and hierarchy, and it was clear that we would never be free under this system, despite winning various reforms from the Civil Rights period.

So, I began to write about a new theory of Anarchism and the Black Revolution of the 1960’s, which had been unfurling in that period and challenging all of racist America with a new world. That period also produced the Attica Rebellion, primarily led by Black prisoners, which radicalized myself and prisoners all over the country, as well as millions who saw it play out on television, and began to understand for the first time the depth of racism and repression in this country’s prisons. A new movement came into existence almost overnight. It became a prison abolitionist campaign, which opposed prison as an institution, and understood it as a crime against humanity itself, and the very extension of slavery. It fought for the human rights of prisoners, even though it understood prisons themselves had to be dismantled and defunded.

So beginning in 1969, when I was locked up, I was an Anarchist, but I wrote the book, however, to give oppressed Black and colonized peoples a voice that did not exist in the contemporary Anarchist literature, or in the movement itself. The book was the door to introduce new ideas, tactics, and motivations. It was the first step towards Black Anarchism as an autonomous full-fledged theory and movement.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

The book has gone through three other printings and is scheduled for a new edition in October 2021. The first edition dealt with a defense of Anarchism from the state, Marxist-Leninist political rivals, and from certain Anarchists themselves, who wanted to raise an idealist, middle-class, white cultist and lifestylist movement. I put forth Anarchist socialism, Black liberation, anti-colonialism, and anti-racism in opposition.

By the second and third editions, the book had changed from an anarcho-socialist economic argument to the ideals laying the foundation of Black Anarchism,which is just really beginning to become popular today as a cultural and political force. I began building on the ideals of Black Autonomy, (Black liberation and Anarchism). In 1994, I worked with some Black college students and community activists to create the first Black Anarchist group, Black Autonomy Collective in Atlanta, Georgia. At one point, it had chapters in ten cities and three other countries. Without the efforts of myself with the book, and others in the Black Autonomy movement to popularize Black Anarchism, it may not have appeared. I say that not as self-gratulation, but as a fact. Someone or some group has to pioneer a new movement for others to rally around.

Why are these new Anarchist ideas needed in this period? For many years state socialism has been in deep crisis. During its authoritarian rule, it created many abuses, and crushed the rights and aspirations of workers and the poor of its own countries. We need a new way to understand the ecological, social and political crisis today. We need to organize from below, to empower the lowest level of workers and oppressed peoples, if socialism is to appear as a revolutionary force in the USA, as well as in other countries.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

My book is an attack on doctrinaire ideology, racism, and capitalism and the abuses of the nation state. It puts forth another view of socialism, libertarian or self-governing socialism, to that of the state. It puts forth a new approach of Black freedom. I want activists and theorists of this period to go beyond orthodoxy, sectarianism, shallow thinking, and conventional politics. We must think and rethink our politics, and not continue to exist in the ditch of bourgeois theory. All social change must not be based on idealism, careerism, or political opportunism. Materialism alone should be rejected as the *only motive force for social change.

It is important to create new movements and Left ideologies, living alternatives to all forms of dogma and rigid orthodoxy.The concept that an idea or theory is immutable and anchored in time forever is totally ludicrous. Anti-revisionism may be good for religion, but not for political activism. We need to be free to engage in praxis.

I am an Anarchist Communist/Black Autonomist, and have many differences with European Anarchism (especially as it exists now), as well as with old school Marxist-Leninist-Maoism, which raised the primacy of the party, state and leadership cult, and engaged in many bureaucratic errors. We can start to build a new society, even while capitalism, the state, and official ideology still exist. Make no mistake, capitalism and the nation-state must be dismantled, but we must create forms of socialism and a mass revolutionary culture until then.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

My ideological mentor was Martin Sostre, who in the 1960’s and 1970’s was one of the best known political prisoners in the world. He was also a Black Anarchist, and gave me many of my foundational concepts after I met him in New York federal detention center upon my arrest in Germany, and being returned to the USA for hijacking a plane to Cuba in 1969. After years in prison on a racist frame-up, Sostre was given clemency by the New York State governor in 1974. He believed that Anarchism is a universal political theory, instead of a white cultural and political tendency. I have let that central idea, and his ideals about libertarian socialism guide me for decades.

Yet, I realize there is no ideology alone that will automatically free people. It has to be based on the desire of the people themselves for freedom, and their ability to carry out their will for revolutionary social change.. In the early stages of any new movement or ideology, it may seem to be purely speculation, but it is always based on the balance of forces, the historical moment, and the crisis of the ruling class, and the willingness of the masses of people to fight back and win.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

There is now a deep planetary crisis (climate change); economic crisis (collapse of capitalism); the death spiral of the nation-state; and the rise of fascist barbarism. The nation-state cannot resolve these problems, and state socialism is an utter failure. Yet, socialism and communism have always been seen as the way forward as alternate economies. I have generally supported these theories, but only in relation to Anarchism as self-governing, anti-bureaucratic programs leading to a future society. Such a society would be against capitalism, dictatorship, war, racism, imperialism, police, and prisons. No government, no dictatorship. A new society entirely.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.

Leave a Reply