Zig Zag on Idle No More: "In any liberation movement there are internal and external struggles"

We are living in exciting times, with large numbers of people clearly fed up and taking action, no longer content to wait for the right moment or the right ideas or the right leadership to tell them what to do. Whether we think of Occupy, the Arab Spring, or the current Idle No More upsurge, spontaneity and taking a stand seem to be the order of the day. For those of us have lived through less exuberant times, it is a welcome change. That said, this new environment that clearly comes with its own potential pitfalls and weaknesses.

In order to try and understand this better, i asked some questions of Zig Zag, also known as Gord Hill, who is of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation and a long-time participant in anti-colonial and anti-capitalist resistance movements in Canada. Gord is the author and artist of The 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance Comic Book and The Anti-Capitalist Resistance Comic Book (published by Arsenal Pulp Press) and 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance (published by PM Press); he also maintains the website WarriorPublications.wordpress.com.

Here is what he had to say…

K: What are the living conditions of Indigenous people today within the borders of what is called “canada”?

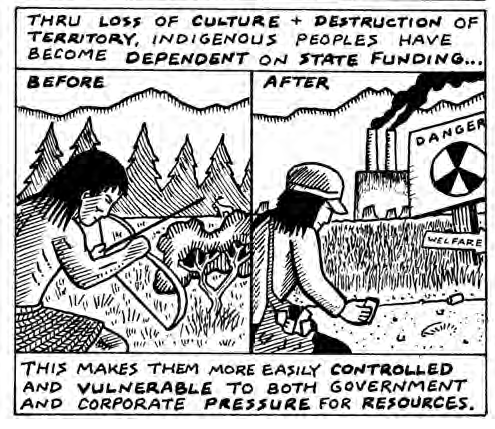

ZZ: Indigenous people in Canada experience the highest levels of poverty, violent death, disease, imprisonment, and suicide. Many live in substandard housing and do not have clean drinking water, while many territories are so contaminated that they can no longer access traditional means of sustenance. In the area around the Tar Sands in northern Alberta, for example, not only are fish and animals being found with deformities but the people themselves are experiencing high rates of cancer. This is genocide.

K: Dispossession has been a central feature of colonialism and genocide within canada. Can you give some examples of how people have resisted dispossession in the past?

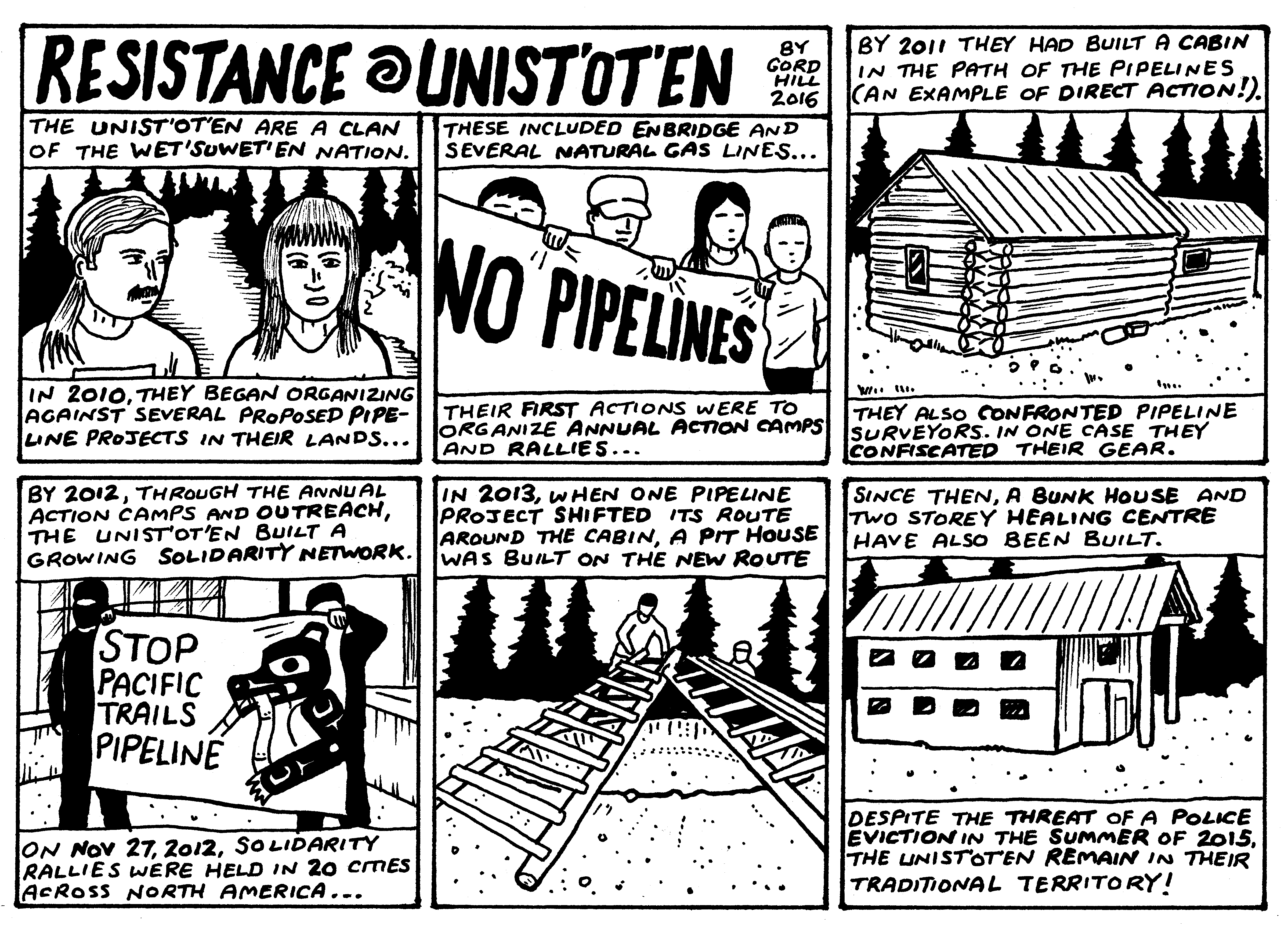

ZZ: Well in the past Native peoples had some level of military capability to resist dispossession, which ended around 1890. More recently there have been many examples including Oka 1990, Ipperwash 1995, Sutikalh 2000, Six Nations 2006, etc. At Oka it was armed resistance that stopped the proposed expansion of a golf course and condo project. At Ipperwash people re-occupied their reserve land that had been expropriated during WW2, and they still remain there to this day. At Sutikalh, St’at’imc people built a re-occupation camp to stop a $530 million ski resort. They were successful and the camp remains to this day. At Six Nations they re-occupied land and prevented the construction of a condo project.

K: The canadian state has an army, prisons, police forces, and the backing of millions of people – not to mention the fact that it is completely integrated into world capitalism, both as a major source of natural resources and as an imperialist junior partner, messing up peoples around the world. What kind of possibilities are there for Indigenous people to successfully break out of this system, and resist canadian colonialism? What is the strategic significance of Indigenous resistance?

ZZ: Indigenous peoples must make alliances with other social sectors that also organize against the system. The strategic significance of Indigenous peoples is their greater potential fighting spirit, stronger community basis of organizing, their ability to significantly impact infrastructure (such as railways, highways, etc, that pass through or near reserve communities) and their examples of resistance that can inspire other social movements.

K: What are bills C-38 and C-45, and how do they fit into the current global economic and political context?

ZZ: Bills C-38 and C-45 are omnibus budget bills the government has passed in order to implement its budget. They include significant revisions of various federal acts, including the Navigable Waters Protection Act, environmental assessments, and the Indian Act. These are generally seen as facilitating greater corporate access to resources, such as mining and oil and gas. The amendments to the Indian Act affect the ability of band councils to lease reserve land. The move to open up resources, by removing protection from many rivers and lakes and “streamlining” environmental assessments is clearly meant to bolster Canada as a source of natural resources and to overcome public opposition to major projects such as the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline and others.

K: Is this something new, or more of the same old same old from the canadian state?

ZZ: These bills are new in that they’re designed, in part, to facilitate greater corporate access to resources, primarily in the changes to the environmental assessment and Navigable Waters Protection Act. These are measures designed to re-position Canada as a major source of oil and gas for the global market, and particularly Asian markets, while diversifying Canadian exports of such resources away from a US focused one, as the US economy continues to decline. At the same time they are indeed a continuation of policies adapted by the federal government for many years now, which include major projects such as the Alberta Tar Sands and proposed pipeline projects. These policies are the result of the neo-liberal ideology that states have been following for the past few decades.

K: What is one to make of this Idle No More movement that has sprung up over the past six weeks?

ZZ: It’s similar to Occupy in that it reveals a yearning for social change among grassroots Native peoples, but it is also reformist and lacks any anti-colonial or anti-capitalist perspective. It is fixated primarily on legal-political reforms, specifically repealing Bill C-45 (which passed in mid-December). Although it has mobilized thousands of Natives, this is only to create political pressure on the government. The four women from Saskatchewan who founded the movement are lawyers, academics, and business managers, so it is no surprise that the entire trajectory of the movement has been focused on legal-political reforms. Another prominent speaker on behalf of INM has been Pam Palmater, a lawyer and Chair in Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University. Last summer, she campaigned against Shawn Atleo for the position of “grand chief” of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN).

As it isn’t anti-colonial or anti-capitalist, it has been a safe platform for many Indian Act chiefs and members of the Aboriginal business elite to participate, and many have in fact helped orchestrate the national protests and blockades that have occurred. In fact, INM allied itself early on with chiefs from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. It was chiefs from these provinces that made the symbolic attempt to enter the House of Commons on Dec. 4, an event that in many ways really launched INM and built the December 10 day of action.

These chiefs oppose Atleo, support Palmater, and have been the driving force behind most of the major rallies and blockades that have occurred in their respective provinces (with notable exceptions, such as the Tyendinaga train blockades).

The involvement of the band councils has helped stifle any real self-organization of grassroots people. The reformist methods promoted by the original founders has included the imposing of pacifist methods and so has dampened the warrior spirit of the people overall. Another factor in the INM mobilizing has been the fast carried out by the Indian Act chief Theresa Spence in Ottawa. This has motivated many Natives to participate in INM due to the emotional and pseudo-spiritual aspects of the fast (a “hunger strike” to the death). Despite the praise given to Spence, she revealed her intentions in late December when she made a public call for the chiefs to “take control” of the grassroots.

K: What you are outlining seems to be a class analysis of the INM movement. Some people have suggested that class analysis is incompatible with anticolonial analysis, that it is divisive, or amounts to applying a european framework that is not relevant to Indigenous people. What do you make of this?

ZZ: Under colonization the capitalist division of classes is imposed on Indigenous peoples. The band councils and Aboriginal business elite are proof of this. Under capitalist class divisions, there are new political and economic elites that are established and who have more to gain from assimilation and collaboration, despite any movements for reform they may be involved in. As separate political and economic elites, they have their own interests which are not the same as the most impoverished and oppressed, which comprises the bulk of Indigenous grassroots people. Middle class elites are able to impose their own beliefs and methods on grassroots movements through their greater access to, and control of, resources (including money, communications, transport, etc.).

For a genuinely autonomous, decentralized and self-organized Indigenous grassroots movement to emerge, the question of middle-class elites, including the band councils, must be resolved. I would also say that in any liberation movement there are internal and external struggles. The internal one determines the overall methods and objectives of the movement, and therefore cannot be silenced or marginalized under the pretext of preserving some non-existent “unity.” In fact, only when internal struggles are clarified can there be any significant gains made in the external one, against the primary enemy (state and capital).

K: January 11 was the day that Harper was initially supposed to meet with Spence and other chiefs from across canada. But on the day of the meeting, due to Harper’s shenanigans, Spence and most other chiefs opted to boycott it, and Spence declared she would be continuing her hunger strike. How deep is this split, and does it signify that some chiefs are breaking with the neocolonial setup and developing a radical potential?

ZZ: There have always been divisions within the AFN and between regions. As I mentioned, some Indian Act chiefs, especially in Saskatchewan, Ontario and Manitoba, have been spearheading many of the Idle No More rallies and breaking from the AFN’s agenda. This shouldn’t be interpreted as proof that they are more radical, but rather that they have their own agenda. “Grand chief” Nepinak of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, the AFN’s provincial wing, has been very active in promoting INM rallies and blockades, etc. But Nepinak’s AMC also suffered massive funding cuts announced in early September. His organization will see their annual funding cut from $2.6 million down to $500,000. He is fighting for his political and economic career and has little to lose by agitating for more grassroots actions, but that doesn’t mean he’s now a “radical.” Rather, the band councils and chiefs must be understood as having their own agenda in regards to their power struggle with the state. Many are easily fooled by militant rhetoric and symbolic blockades, but these are old tactics for the Indian Act chiefs.

Along with chiefs fighting for the maintenance of their provincial or regional organizations (such as the AMC or tribal councils), which is contributing to band council participation across the country in INM mobilizing, the chiefs in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario have a political struggle with Atleo and have their own vision for greater economic development. It was the chiefs from these provinces that boycotted the meeting between the PM and Atleo, and who called for the January 16 national day of action.

Delegations of these chiefs have travelled to Asia, Venezuela, and Iran seeking corporate investors, especially in the oil and gas industry. Chief Wallace Fox of the Onion Lake Cree Nation, one of those at the forefront of recent events and an outspoken opponent of Atleo, is the chief of the top oil producing Native band in the country (located in Alberta and Saskatchewan). Fox and other chiefs have also attempted to gain access to OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, for partnerships with corporations. Nepinak and other chiefs also met with Chinese officials in December, also looking for potential partnerships.

The rationale of these chiefs, Palmater and their allies in INM (the four “official founders”) is that Atleo is collaborating with the assimilation strategy of the Harper regime. Meanwhile, it is they who seek to take control of the AFN and impose their own version of Native capitalism, based in part on foreign investment in resource industries. Ironically of course, many INM participants are rallying to defend Mother Earth, in many ways being used as pawns in a power struggle between factions of the Aboriginal business elite. Many INM participants, I would say, are unaware of these internal dynamics. Their mobilization under the slogans of “stop bill c-45,” “defend land and water,” etc., are positive aspects of INM, and show the great potential for grassroots movements. But this is something that is in the early stages, and the movement will have to overcome the parasitical participation and control of the Indian Act chiefs as well as middle-class elites for it to advance.

K: There were hundreds of Idle No More actions on January 11. Here in Montreal, roughly three thousand people demonstrated, by far the largest protest related to Indigenous issues i have ever seen in this city. At the same time, the demonstration was overwhelmingly made up of non-Indigenous people, ranging from radical anticapitalists to members of Quebec nationalist and social democratic groups. This seems in line with the INM strategy of framing the movement as representing all canadians. How compatible is this with an anticolonial perspective, and what are the strengths and weaknesses of such diverse support?

ZZ: The first priority and main focus for an anti-colonial liberation movement must be its own people. This is how it develops its own autonomous methods and practise, free from outside interference. This helps to unify the movement and establish it as an independent social force. Alliances are clearly necessary, and while the ultimate goal might be a multi-national resistance movement, colonialism and the unique history as well as socio-economic conditions of Native peoples means they must be able to organize autonomously from other social sectors.

I think in principle to frame Idle No More as one representing all Canadians is correct, but the way in which they are doing this waters down and minimizes the anti-colonial analysis that is necessary for radical social change. By trying to appeal to the “Canadian citizen” it may broaden its appeal but to what end? In the process it will have weakened the anti-colonial resistance. Even now you can see the renewed calls for “peaceful” protests from INM’ers, as well as statements from the “official founders” that they don’t support “illegal” actions such as blockades. They’re very sensitive to any loss of public support, claiming it is now an “educational” movement and that they don’t want to inconvenience citizens. The reformists might claim that in this manner we can build a bigger movement to defeat Bill C-45, but clearly such bills are just part of a much larger systemic problem we can identify as colonialism and capitalism. Without addressing the root causes we’ll just be doing the same thing next year against another set of bills. And of course, basing one’s anti-colonial resistance on the opinion of the settler population will never lead to liberation.

K: We seem to have entered a period of spontaneous upsurges like INM internationally, be it the Arab Spring or Occupy or the recent anti-rape protests in India; in each of these cases masses of people are clearly fed up and willing to throw themselves into action, but for better or for worse they often bypass any of the organized anti-imperialist or anti-capitalist groups or traditions. Is this a sign of a failure on our part, that when circumstances finally give way to revolt we are not connected to those doing the revolting? Or is there something else going on?

ZZ: I would say a part of these mobilizations is the use of social media in spreading information and coordinating actions. Certainly in the Arab Spring, Occupy and now Idle No More, this has been a significant component of the mobilizing that has occurred. It seems that there are more people who have been influenced by these ongoing social revolts and mobilizations, that then decide to take action of some kind, and the internet empowers them to organize rallies, etc. They don’t need the already existing radical groups to do this, and may not even know of their existence.

This leads to the situation where mobilizations are called, gain traction and then expand — but they have a very shallow analysis of the system and lack experience in real resistance. In both Occupy and INM we see inexperienced organizers who believe they have re-invented the wheel, who feel they know best how social movements should conduct themselves, etc. At best, these mobilizations show that there is a yearning for social change among a growing number of people, but social media enables them to bypass more experienced and radical groups, and their naivete leads them to think that these groups fail because they’re too radical. Therefore they appeal to the most basic and populist slogans, the least threatening forms of action, etc.

I don’t know if I would characterize it as a failure on the part of radical groups that they are somewhat disconnected from these types of mobilizations. They’re not revolts, they’re largely reformist rallies without a radical analysis dominated by liberals and pacifists, middle-class organizers, etc. Until these movements are radicalized there is little possibility for radicals to be fully involved. Another aspect of these types of mobilizations is their relatively short duration. Occupy was largely over three or four months after it began, with some exceptions (such as Oakland). How long will INM endure?

K: Although their leadership may be neo-colonial and middle-class, surely many of those in the grassroots who are attracted to surges like INM are not. How should established Indigenous anti-colonial groups relate to these mass mobilizations? Are there specific approaches that are more effective than others? And are there things to avoid?

ZZ: I would say Indigenous anti-colonial groups should engage such movements critically, and not simply take the role of cheerleaders. When large numbers of people are aroused and mobilized, it means they’re thinking about, and discussing, concepts such as colonialism, tactics, strategies, methods, etc. So it is an opportune time to contribute radical anti-colonial and anti-capitalist analysis, even though some participants in the movement think that such debate “divides” people. I would avoid denouncing such movements, or opposing them, of course, because there are both positive and negative aspects. Promote the positive and try to illuminate the negative, the contradictions, etc. As many participants are new and inexperienced, anti-colonial groups can contribute a lot to expanding and radicalizing the movement.

Leave a Reply