Love for Our People: David Gilbert’s No Surrender (reviewed by Chris Crass)

I cry quite often at movement events these days. In political marches, looking out at the delegations and contingents of people from churches, unions, community groups and schools. At conferences, when people speak about how much they love their community and organizations. When I saw the first person jump over the fence to protest against the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, the tears ran down my face as I held hands with the Unitarian Universalist activists I was with. I cry because as I get older, my appreciation for the dedication, hardship, necessity and beauty of left/radical struggle in the world has deepened tremendously. I cry because as more and more of my comrades have children, the next generation whose futures we fight for are real people with names and personalities rather then a rhetorical concept. I cry because as I begin to say good-bye to loved ones of the older generation who are passing, I realize just how much they have done for us and how much we have to live up to.

I cry quite often at movement events these days. In political marches, looking out at the delegations and contingents of people from churches, unions, community groups and schools. At conferences, when people speak about how much they love their community and organizations. When I saw the first person jump over the fence to protest against the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, the tears ran down my face as I held hands with the Unitarian Universalist activists I was with. I cry because as I get older, my appreciation for the dedication, hardship, necessity and beauty of left/radical struggle in the world has deepened tremendously. I cry because as more and more of my comrades have children, the next generation whose futures we fight for are real people with names and personalities rather then a rhetorical concept. I cry because as I begin to say good-bye to loved ones of the older generation who are passing, I realize just how much they have done for us and how much we have to live up to.

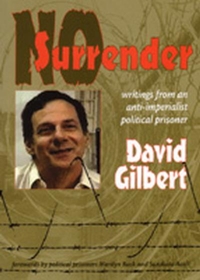

Preparing this review of David Gilbert’s new book, No Surrender: writings from an anti-imperialist political prisoner, I thought about my place in a multigenerational movement and my relationship to the older generation of left/radicals. Three community events stand out for in preparing this review: sitting in the Castro Theatre years ago, at the premiere of “Out: the Making of a Revolutionary” about Laura Whitehorn; the release of Marilyn Buck’s poetry across prison walls CD “Wild Poppies”; and the book release party for No Surrender. All three events for these white anti-imperialist political prisoners drew large multigenerational crowds of left/radicals that felt like reunions, even though I didn’t know most of the people. For me, as a younger generation white left/radical committed to anti-imperialism and feminism, there is something spiritual about these events as I recognize I am part of this legacy. These political prisoners are among my many leaders. As a white male struggling to negotiate what it means to fight with love for all people, challenge privilege and develop an affirming and healthy identity, David Gilbert holds a special place in my heart — not because I uncritically see him as a role model, but because of his commitment to liberation and ability to openly evaluate his work.

Gilbert came of age politically during the Civil Rights movement, which he explains, “showed me more of a sense of humanity and nobility of purpose than I found in the white suburbs where I had grown up.” In 1962, he joined CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, and in 1965 started up the Committee Against the War in Vietnam at Columbia University. He co-founded Columbia’s Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter, wrote an influential national pamphlet for SDS on U.S. imperialism, and participated in the 1968 Columbia strike against the war. He was one of a small number of men who responded pro-actively to the emerging Women’s liberation movement and continued to act in solidarity with the Black freedom movement.

In the early 70’s he helped form the Weather Underground Organization (WUO) that took up arms against the US government. According to Gilbert, they formed “in response to the murderous government assault on the Black Liberation Movement and the unending, massive bombing of Vietnam.” He spent 10 years in underground resistance and he was arrested on October 20, 1981, when a unit of the Black Liberation Army and allied white revolutionaries attempted to take money from a Brinks truck. There was a terrible shoot-out that left a guard and two police officers dead. A member of the BLA later shot and killed. Many others were arrested and given long sentences. David Gilbert is over 20 years into his 75-to-life sentencing. His earliest parole eligibility is 2056. No Surrender is a collection of Gilbert’s writings over the past 20 years.

Gilbert’s writing are based in his experience as a committed left/radical who has taken significant and controversial positions about strategy — particularly regarding armed struggle. He has put his positions into practice and has helped make movement history over the past 40+ years. What is most noteworthy about Gilbert is his open and honest evaluation of himself, the organizations he was part of, the mistakes he and they made, and the lessons identified for organizing today.

Maria Poblet, a queer Latina tenant organizer in San Francisco, emphasizes this point, “David Gilbert’s book and life are flares in the darkness – they can help guide our generation towards the vision and commitment we need for the revolutionary transformation of our world. His insights into imperialism and white supremacy and his personal example of solidarity agitate and inspire me in my community organizing and movement building efforts.”

No Surrender brings together essays, extensive book reviews, short stories about his son Chesa Boudin, and interviews. For anyone who hasn’t read Gilbert’s essays, there are some really exciting pieces. “Looking at the White Working Class Historically” asks hard questions about the roles of white working class people in the development of capitalism and white supremacy. While recognizing that white supremacy has consistently led working class white people to identify as superior to people of color, Black people in particular, he identifies ways that white working class people have participated and will participate in anti-racist, multiracial efforts to win justice for all people. “Coming of Age Politically at Columbia” and his short essays on SDS and WUO are excellent examples of the kind of reflection that is needed. They give us insight into how he and the organizations he was part of made their assessments of what to do next. How did they understand their circumstances historically and politically? What were the possibilities and opportunities that they identified? This is followed, most importantly, with critical evaluation looking back for insights and lessons. The interviews assembled throughout the book are key reflections on past work guided by the goal of presenting lessons in the clearest way possible.

The book is organized into themes. The section “Lessons to Liberate the Future” is a solid collection of his reflections and lessons. He speaks to activists today about what he believes needs to be done. He argues, “Our job is to keep alive a vibrant voice and a clear opposition, in both our politics and our lives, to all forms of oppression; and a deep sense of history of the protracted nature of the struggle ahead.” In other sections, he uses book reviews to break down the core information and analysis of the books and present his own thinking. Over and over again, these reviews offer insightful reflection and sharp analysis about challenging male supremacy, imperialism, AIDS, popular social movements and ending white supremacy.

Overall, Gilbert is at his best when giving frank responses to questions about his past activism and lessons for today. A primary example is his expressed regret and sadness about the killing of the security guard, the two police officers, and his comrade in October of ’81. His critiques of the Leninist model of organization, male supremacy, egotism, and sectarianism in the Weather Underground are crucial for thinking about activism today. He also models an honest and balanced approach to critique, speaking about successes and genuine achievements that need to be remembered as well.

Heidi Reijm, a member of the white anti-racist affinity group Ruby in New York City, highlights this aspect of Gilbert’s work. She writes: “David Gilbert is an incredibly giving, compassionate person, and this book represents his life-long dedication to the struggle for social justice. His life is an inspiration and resource to us who continue anti-racist work today. Gilbert also teaches us about the seriousness of the choices we make. We learn important lessons from his activities that cost people’s lives and cost the movement the good that David could have done on the outside.”

While there are important lessons in it and much to like about the book, the fact that it is mostly book reviews written for the general reader meant that it often didn’t go deep enough. I wanted more autobiography and more discussion of what led him to make the decisions he did: how did people decide to move to armed struggle? How did they conceptualize and actualize their strategy day-to-day? And how did they see themselves in relationship to the broader movement? For younger generation white anti-racists it is critical to get a serious evaluation of how white guilt and class guilt played out in WUO and what concrete impacts it had on strategy. How did it get to the point where WUO advanced the slogan “Fight the People” (meaning white people) and actually gave initial support to the Manson Family? Because the Weather Underground championed white anti-racist work and they have significant influence, serious examination of the political conditions and strategic assumptions is critical. Nevertheless, it is a good sign when one wants more from an author.

I also agree with a review Michael Novick of Turning the Tide wrote that it would be useful for Gilbert to engage more with the anarchist, anti-authoritarian politics that have become central to many younger generation activists. His perspectives on imperialism and national liberation would be very helpful in developing anarchist politics. I also think anarchist politics would help develop his critiques of hierarchical organizing and present new models to contemplate. As younger generation left/radicals, like Maria Poblet, Heidi Reijm, myself and tens of thousands of others, continue to develop new syntheses of different political traditions, we need insights, lessons and contributions from our mentors. Additionally, we bring our own experiences, reflections and analysis to these efforts.

Gilbert’s writings are important for younger generation activists in general and in particular to white activists. If you haven’t read much about the Civil Rights movement, the Women’s Liberation movement and other broad-based movements, I strongly encourage you to dig in and commit to serious study. The movements of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s advanced liberation on a wide range of fronts. The more that younger generation left/radicals study and engage the history and the people, like Gilbert, who made it, the more we will be able to bring about the revolutionary changes that live in our hearts and grow in our organizations and communities. In his Haiku “Our Politics in 17 Syllables”, Gilbert explains, “love for our people / means nonstop struggle against / imperialism”. It is this love that makes me cry at movement events and it is his love that makes him such an important leader for today.

No Surrender: writings from an anti-imperialist political prisoner By David Gilbert published by Abraham Guillen Press/Arm the Spirit Available from AK Press, 283 pages, $15.00

For further study:

Enemies of the State: Interviews with Marilyn Buck, David Gilbert and Laura Whitehorn by Resistance in Brooklyn, 74 pages.

Available from AK Press David Gilbert: A Lifetime of Struggle. 28-minute video interview with David Gilbert in prison. Produced and distributed by Freedom Archives, info at freedomarchives.org

Out: The Making of a Revolutionary, the story of Laura Whitehorn. Full-length documentary also available from Freedom Archives.

Special thanks to the editorial team on this review: Clare Bayard, Chris Dixon, Jeff Giaquinto, and Sharon Martinas. Chris Crass is the coordinator of the Catalyst Project, a center for political education and movement building. They focus on anti-racist work with mostly white sections of the global justice and anti-war movements with the goal of deepening radical commitment in white communities and building multiracial left movements for liberation.

Leave a Reply