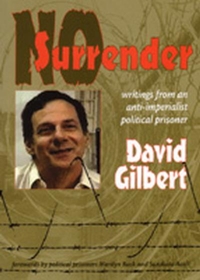

No Surrender: Writings from an Anti-Imperialist Political Prisoner, by David Gilbert, Reviewed by Michael Novick, Editor, Turning the Tide

You may know David Gilbert from his appearance in the recently popular, award-winning documentary “Weather Underground,” which has played in art houses around the US and is now available on DVD. If so, you know he is a warm, engaging, committed, optimistic and insightful person, capable of unflinching self-criticism but unyielding in his sharp critique of the empire, of white and male supremacy, genocide and exploitation. If you haven’t seen that film, or the video “David Gilbert: A Lifetime of Struggle,” you should definitely get them or see them, as well as buying and reading this book of his perceptive articles and book reviews.

You may know David Gilbert from his appearance in the recently popular, award-winning documentary “Weather Underground,” which has played in art houses around the US and is now available on DVD. If so, you know he is a warm, engaging, committed, optimistic and insightful person, capable of unflinching self-criticism but unyielding in his sharp critique of the empire, of white and male supremacy, genocide and exploitation. If you haven’t seen that film, or the video “David Gilbert: A Lifetime of Struggle,” you should definitely get them or see them, as well as buying and reading this book of his perceptive articles and book reviews.

“No Surrender” is a stimulating, wide-ranging and important collection of essays, interviews and reviews by a Euro-American anti-imperialist political prisoner. David Gilbert is a former member of SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) and the Weather Underground Organization (WUO). He’s serving a long sentence in state prison in NY for participation in an expropriation by the Revolutionary Armed Task Force of the Black Liberation Army (BLA), in which lives were taken and lost. David has been an AIDS activist behind prison walls for years, as well as a book reviewer from 1992-97 for ‘Downtown’ and its sister publication. David selected and slightly edited writings from a span of over 20+ years, beginning with his trial statements in 1982 and 1983, and concluding with reflections on the anti-war movement post-9/11 and in the wake of Bush’s pre-emptive Iraq War. The material is not organized chronologically but thematically (although the opening section does include a memoir of his days in the New Left leading into the WUO, followed by the court pieces. These make clear where David is coming from, why he is a political prisoner, and the body of theory and practice from which his prison writings emerge).

In the interest of full disclosure, I should acknowledge that I have known David personally both before and since the events that made him a political prisoner. I too, was active in SDS in the same period as he, was active in defending him and the other RATF prisoners when they were put on trial, have corresponded with him occasionally since he has been behind bars. I in fact published an early version of one of the pieces included in this book, “AIDS Conspiracy Theories: Tracking the Real Genocide,” in Turning the Tide. (David cites my own book, White Lies White Power, in that article.) So in engaging the material in this book, I am not a disinterested critic, but a comrade committed to winning freedom for David Gilbert and all political prisoners and POWs, and to creating a better society and world to replace the imperialist system in which we live.

One strikingly positive aspect of the book is David’s striving to integrate understandings about class and male supremacy into his grounding in support for national liberation and opposition to white supremacy. His appreciation for women’s role in struggle and in life, as well as for the central importance of women’s liberation to any effort to remake the world, shines through the whole volume. It extends beyond the sections specifically about challenging male supremacy (such as his critique of Robert Bly’s “Iron John,”) and about considering the revolutionary truths advanced by women of color (such as his review of Barbara Smith’s “The Truth That Never Hurts.”)

Another particular strength of the book, reflecting David’s practical engagement in direct action strategies for dealing with the devastation of AIDS inside the prison walls, is the material on AIDS in prison and on global health. It is one of the longest sections in the book, and the most original (particularly in the sense that it consists mostly of David’s own direct analysis and theorizing, as opposed to reviews of others’ work). It poses a tremendous challenge to us to deal with the genocidal impact of the AIDS plague in Africa, Asia and among African and indigenous/’Latino’ people in the U.S. This segues logically into a section on the nature of imperialism globally and then into reflections on current popular struggles for human rights and de-colonization.

However, It would be a disservice to David and to the cause of human liberation to which he has given so much and to which he continues to devote himself, to simply praise the book and what he has to say in it. David is striving to engage himself and us in a continuing revolutionary process, defying the prison bars that contain his body but not his loving heart, inquiring mind or indomitable spirit. His writings, and their publication in book form, are a tremendous contribution to the struggle, but they are not meant to be and should not be taken as the ‘last word.’ Rather, they are meant to stimulate thinking, struggle, further study and analysis. David is still trying to understand errors and weaknesses among popular and revolutionary forces that have allowed imperialism to maintain its grip. He wants to figure out how we can do better and win — and we should be doing the same.

In that spirit, in addition to some key strengths of David’s understandings and exemplary theorizing and practical work, I will also look at some weaknesses, some continuing issues that the book in its totality presents for him and for us, requiring further examination and struggle. “No Surrender” is a very meaty, diverse work, looking at movement history, white supremacy and theories of white skin privilege, global capitalism, African oppression and liberation, AIDS, women’s oppression, resistance and liberation, lessons for the future, as well as some personal and political humor and children’s stories. Most of it is presented through the prism of reviews of other people’s work, which David summarizes and critiques succinctly and effectively. As such, it merits two or three readings. You may want to pursue some of the books and authors he points out, too.

The thematic organization, while it helps to deepen the analysis and exposition of a given topic by grouping several different writings together, sometimes detracts from a sense of the development and transformation of David Gilbert’s thinking over time. In other words, each piece of material does indicate when it was written, but they are not presented chronologically. This is a shame, because David is committed to a historical and material analysis. His thinking has not been static and frozen. It has grown and changed through a process of self-criticism and of engagement in collective struggle behind and through bars, as well as of political activism around new and pressing issues as they have continued to arise since his incarceration. A chronological index might have been a useful addition to this book. If it is reprinted, as it hopefully will need to be, the publishers should consider adding such an appendix, to make it easier to follow that process by reading articles in sequence from the 80’s, 90’s and post-2000.

The book also offers valuable explications of the nature and origin of white supremacy and the key role it plays in the maintenance and propagation of imperialism. David reflects on Ted Allen’s “White Supremacy in the U.S.”, “Black Reconstruction” by WEB DuBois, J. Sakai’s “Settlers: The Myth of the White Proletariat,” and “Night Vision” by Butch Lee & Red Rover. It should lead the reader unfamiliar with this material to read those important volumes in their entirety. Compare your own critical assessments of the books with David’s evaluation of their strengths and weaknesses. David also very effectively surveys material on the transformations taking place economically in the imperialist system, sometimes referred to as globalization. He highlights the important political economic understandings about the deepening exploitation of the global South that such analysis has provided. He also critiques weaknesses of not fully grounding such exposes in revolutionary opposition to the imperialist system as a whole (as in his reviews of works by Walden Bello and Kevin Danegher, among others).

There are however, a number of weaknesses in some of the articles in the volume, some more troubling than others. One is that David Gilbert nowhere grapples with anarchism — in fact, I don’t think the word anarchism appears in the entire volume. Although he is critical of Stalinism, as the New Left was, he does not draw out deeper lessons from some of the struggles he reflects on. He remains convinced that what he describes as a disciplined combat organization is essential to the process of liberation. David reflects on the crimes of regimes like that of Pol Pot in Cambodia, laments the dictatorial and capitalistic turn of “Communist” China, and discusses the desire on the part of the Zapatistas in Mexico and the forest workers in Brazil to avoid hierarchical vanguard approaches. But David nowhere in this volume expresses a thorough critique of either vanguardism or the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat.’ Nor does he address anarchist critiques of such concepts.

This is somewhat surprising, since he dedicates the book in part to his comrade Kuwasi Balagoon of the BLA, to whose death from AIDS he also credits his involvement in struggling over AIDS issues in prison. Kuwasi Balagoon was a self-proclaimed anarchist whose advocacy of that was a central element of his (Balagoon’s) writing both before and after his incarceration. Most people of a younger generation than David who will be interested in this book are probably anarchists or influenced by anarchism, and even if Gilbert discounts such politics, you’d think he would have been exposed to them and want to address them. If he believes anarchism is a dead end, he should state so forthrightly, respond to its critique of Marxism and Leninism, and provide his countervailing arguments.

There are also strengths and weaknesses in his treatment of the WUO. David is correct in emphasizing the positive aspect of the WUO’s willingness to build a clandestine armed resistance to imperialism, and his critique of its errors is equally important. He states: “The downfall (of the WUO) came from drifting back into the traditional failures of the white Left with the politics of the ‘multinational working class,’ and a plan to be central to ‘leading’ the ‘whole U.S. revolution.’ These positions negated the independent and leading role of people of color…When those forces sharply criticized us, we — with our vitality sapped by the lack of internal democracy – couldn’t deal with it and instead split apart amid harsh recriminations.”

This presentation is much franker than that made by other leaders of the WUO in the recent documentary film Weather Underground, which attributes the demise of the WUO to fatigue and the end of the war in Vietnam. In fact, as David indicates, the WUO intended to resurface itself as the head of a new communist party, akin to the other similar Maoist party-building efforts such as the Revolutionary Communist Party or Line of March. Denial of the anti-colonial nature of New Afrikan/Black, Mexicano, Puerto Rican and American Indian/First Nations’ struggles was and continues to be a key error of the left.

However, this political error goes hand in hand with doctrines of centralism and ‘two-line struggle’ in which all deviations from the party line are ‘petty-bourgeois errors’ that must be recanted. An authentically anti-imperialist political approach which recognizes and upholds the self-determination and independent, leading role of the anti-colonial struggles of oppressed people — oriented towards smashing the empire and dismantling the federal state — should naturally lead to decentralized and anti-hierarchical forms of organization. But this is not a direction David Gilbert seems to embrace. “As far as I know,” he says, “there is still no clear-cut successful model for combining the two critical needs of a fully democratic internal process and of tight discipline for fighting a ruthless state.” The impulse towards restricting democratic process to an ‘internal’ one, and the blindness to the use of headless networks as a means of fighting and resisting the ruthless state, seem to be interconnected, unexamined weaknesses in his thinking.

A related weakness is in his assessment of what has set back the struggle globally since the beginning of the 80’s. David Gilbert correctly attributes this to a general failure of the struggles for national liberation after the high-water marks of the success of the Vietnamese revolutionary war against U.S. imperialism, and sees this as far more important than the collapse of the Soviet Union and its bloc. But he fails to elaborate fully on the relationship between the weaknesses of the centralized and statist ‘model’ of Soviet socialism, and of the national liberation movements that it backed. Those movements had critical internal weaknesses, related in part to their adoption of the democratic centralist model, as well as to their absorption of the strategy of cross-class unity to seize power that the Soviets encouraged.

Even in succeeding, therefore, such movements proved incapable of leading a thorough and ongoing revolution. Instead, they consolidated power in the hands of new elites, who were then forced to accommodate and compromise with imperialism and global capitalism. Such an analysis is necessary to understanding why the national liberation movements crested and fell back in the face of an imperialist counter-offensive. It is necessary to help guide future liberation struggles so that we can do away with imperialism and all forms of oppression and exploitation once and for all.

Two or three minor weaknesses bear comment. One is his repeated reference to the New Left and anti-war movements of the 1960s and early 70s as “upper middle class.” Gilbert is perhaps focused on his own privileged class background here, and that of some of his closest comrades in the leadership of SDS and the WUO. But the student movement and the anti-war movement, as well as white fighting forces that engaged in armed struggle against the state in that period, were in fact far more diverse in terms of class background than he credits. The Revolutionary Youth Movement strategy articulated by SDS, to organize white working class youth, community colleges and among GIs, was a phenomenon that was already going on by self-organization before they proposed it. As a working class young person from an immigrant trade union family who joined SDS at a less-privileged public college, I can attest to the fact that there were many working class kids in SDS. This was also true in the broader youth movement and anti-war, civil rights and other struggles of the time. The extent to which GIs began turning the guns around, for example, was a key factor in ending the draft and the war. Kids in high schools across NY and many other cities were intensely active and self-organized.

In addition, David Gilbert’s treatment of environmental issues is one of the shortest and least thorough sections of the book, and there is no mention of animal rights and earth defense actions such as those of ALF and ELF activists. An analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of such recent movement, especially in regards to blindness to issues of racism and white supremacy, would be a worthy addition to this book. A political prisoner of David’s stature, with a long history in armed clandestine opposition to the US state, could offer important insights on this issue. Perhaps all this, like the avoidance of anarchism, simply reflects the way in which David has been cut off by the state from some struggles that have gone on since his incarceration.

These struggles and criticisms are not meant to detract from the great contributions David has made and is making to revolutionary struggle. I recommend this book wholeheartedly, as a valuable and living addition to the library of anyone concerned with resisting genocide, ending the empire, and winning human liberation and a sustainable future.

This review appeared in the new Fall 2004 issue of “Turning the Tide: Journal of Anti-Racist Action, Research & Education”, Volume 17 Number 3. Subscribe now to Turning the Tide: Journal of Anti-Racist Action, Research & Education: Anti-Racist Action/People Against Racist Terror PO Box 1055 Culver City CA 90232; tel: 310-495-0299; www.geocities.com/ara_losangeles ; antiracistaction_la@yahoo.com .

Leave a Reply