Orisanmi Burton on the Revolutionaries Organizing Inside Attica Before the Rebellion

From the “Prison Activism and the Organizing Tradition” panel at the Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration Conference, Dec 5th, 2019. The panel also featured Dan Berger, Steven “Stevie” Wilson, Zoharah Simmons, Darren Mack, and Jessica Wilkerson. The full transcript from this and other sessions available at https://mumiconference.com/transcripts/

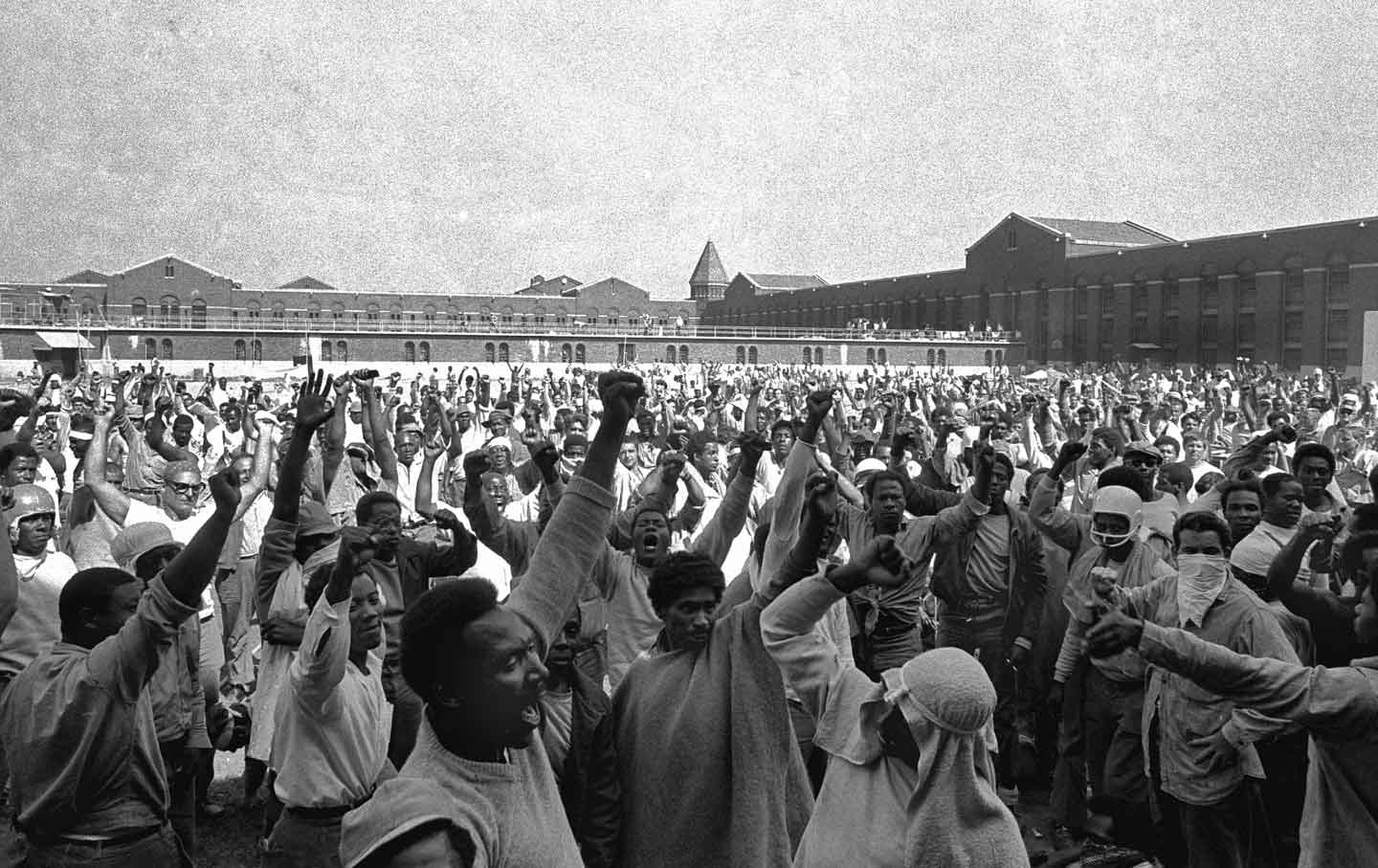

So, what is the conspiratorial explanation of the Attica Rebellion? A few days after the state’s genocidal siege, Prison Commissioner Russell Oswald went on television and said that he had no doubt that the rebellion was instigated by hardcore Maoists. Later on, in his book, Oswald posits that the tactics of this revolutionary prison conspiracy included the following: 1. Articulating specific objectives prior to the uprising. 2. Developing grievances that resonated with the demands of radical organizations outside the walls. 3. Determining, in advance of a rebellion, who would handle food, supplies, and weapons. 4. Calibrating the calculated use of violence and non-violence to have the desired political effect. 5. Organizing “a carefully coordinated confrontation at a set time that was pre-arranged, so that external demonstrators could be synchronized.” 6. The articulation of demands, which the rebels knew prison administrators could not grant, as a deliberate effort to cause dissention within the state government while at the same time building, what he called, convict unity. His 7th and final point was that captive rebels “did not want meaningful prison reform but wanted, instead, to polarize the people of the United States against and for the prisons as a paramount, oppressive instruments of the power structure.” While I disagree with some of the finer points of Oswald’s framing of these tactics, specifically the way in which he strategically over-emphasizes the extent and success of the coordination, in general, I contend that what he is saying is true. And to demonstrate this, I’m going to draw on the Black radical archive of Attica and talk about some of its claims.

Let’s start with the first point: the notion that the rebellion was instigated by Maoists revolutionaries. By 1970, prison authorities estimated that Black Panther groups were present in virtually every prison in New York State, with between 200 and 300 in Attica alone. Like their counterparts in the free world, these captive Panther formations were required to read the BPP’s Eight Points of Attention, which was largely appropriated from Mao’s Red Army Manual, as well as Quotations from Mao Zedong, also known as The Little Red Book. In January of 1971, two years after he was sent to prison, a young Eddie Ellis wrote, “I’ve already made up my mind that there is nothing in this penal system capable of breaking or destroying me. I bend like a weed in the wind. I float like a fish in the sea. I remember Mao and [35:26] and all of the other teachings I have had and fortify it with this knowledge; knowledge of myself and my enemy. I am able to survive, even prosper.” Eddie was one of the men who helped lead the political educations sessions in Attica prior to the rebellion. He was a close comrade with Max Stanford, who was a founding member of the Revolutionary Action Movement. Stanford had made trips to Cuba during the 60s to visit his mentor, Robert F. Williams, who had been an advisor to Mao and an associate of Che Guevara. So, not only were the Attica rebels reading Mao and [36:01] and trying to put these theorists into practice through Eddie and others, they were, at most, three degrees removed from Mao and other leaders of revolutionary movements. The archive is replete with evidence of communication between the Attica brothers and Third World Liberation Movements. I’ll give you two quick examples. First, following the submission of the Attica Liberation Faction Manifesto of demands, a nearly identical document in Vietnamese language was issued by Vietnamese prisoners of war in Côn Son Island Prison in South Vietnam. That was before the rebellion. Second, during the rebellion, the Attica brothers articulated a demand for speedy transportation to a non-imperialist country, which may seem far-fetched today, but at the time, the Black Panther Party had an international section based in Algiers, which was formerly recognized by the Algerian government and was composed mostly of fugitives; many of whom had escaped from prison, hijacked planes, and attained asylum in Algeria. During the rebellion, Safiya Bukhari-Alston, a key New York Panther, secured verbal agreements from leaders in Cuba, North Vietnam, North Korea, Congo Brazzaville, and Algeria to accept the Attica brothers who wanted to leave. She and other members of the so-called Cleaver faction were actively trying to figure out the logistics of making this happen. It didn’t happen, but Attica was a Maoist revolutionary conspiracy.

Next point, the idea that the rebels weren’t really interested in prison reform and that they knowingly made demands that administrators had no ability to authorize. Two examples. The first comes from a document produced in New York’s Auburn Prison in 1970. It’s from the rules and regulations of the Auburn Black Panther Party, who described themselves as a revolutionary action group. Their stated objectives make no mention of prison reform or of improving prison conditions. Instead, it indicates their desire to overthrow the established government of the United States and replace it with a People’s Government that would allow the masses to determine their own destinies. The second example comes from a published source. The prison letters of Samuel Melville, a white Attica brother who, one month before the rebellion, sent a letter to a comrade where he expressed excitement about the political consciousness he saw emerging in Attica; but he wrote that they need to “avoid the obvious classification of prison reformers.” He continued, “when you come right down to it, of course, there’s only one revolutionary change as far as the prison system is concerned. But until the day comes, when enough of our brothers and sisters realize what that one revolutionary change is, we must always be certain our demands will exceed what the pigs are able to grant.” So, we see that prior to the rebellion, some of the rebels were discussing how to tactically deploy unreasonable demands at the same time that they negotiated with the state for the practical proposals, which dealt with improving prison conditions. They had different demands for different constituencies, and this, I believe, is because they knew that what they wanted, what they really wanted—revolutionary transformation, decolonization, and prison abolition—could not be granted by the commissioner, the governor, or the president. Some of their demands were directed to their co-conspirators outside the walls, to you and I.

Point three is Oswald’s contention that this new kind of rebellion involved “a carefully coordinated confrontation at a set time that was pre-arranged, so that external demonstrations could be synchronized.” This was a theory that his administration developed based on several different pieces of information, not least of which occurred on May 8, 1971 when roughly 100 members of Trotskyist organization called the Prisoners Solidarity Committee marched around the prison chanting denunciations of prison slavery and class warfare in protest of the ongoing isolation and torture of those involved in earlier prison rebellion, called the Auburn Prison Rebellion. At the same time that this was happening outside, as the sounds of their chants seeped through Auburn’s dense concrete walls, the men locked inside of Auburn’s special housing unit mobilized a collective housing unit by breaking metal springs from their bedframes and picking the locks of their special housing unit cells. They then weaponized the cell furnishings. As one of the rebels recalled to me in an interview, “we broke the porcelain sinks off the walls to make shards as sharp as razors and threw the shards at the police as weapons.” Nearly five decades later, this person has no recollection of this being a coordinated plan, but that doesn’t matter because it happened. And things like this continue to happen in different ways because the relationship between the inside and outside movements have become so intimate that they were causing simultaneous disorder on both sides of the walls.

Last point, the calculated mobilization of violence and nonviolence to have the desired political effect. The first thing you should know is that prior to the rebellion, the rebels began organizing what they called tactical intelligence and combat units that were essentially preparing to carry out guerilla warfare. The next thing you should know is that during the rebellion, the rebels chose to treat the prison police, who were now hostages, better than the police had treated them. The lack of retaliatory violence is usually attributed to the discipline and values of the Nation of Islam, which is definitely part of the story; but according to Attica brother Dalou Gonzalez, a member of the Young Lords Party, the decision to treat hostages kindly was guided by Mao Zedong thought in the edict that guerilla forces should always give lenient treatment to prisoners of war as a way to disintegrate enemy troops. So, the tactical use of violence and nonviolence was not a moral imperative, but rather a political strategy employed to delegitimize the carceral warfare state. And you actually see this happening. After the state’s genocidal siege of Attica, there are guards who go on record saying that they didn’t sign up to be treated as disposable. And so, people on both sides of the walls exploited this and tried to highlight this to show white folks and people who supported police that they were also disposable under this carceral regime. So, that was actually a pre-determined strategy.

Leave a Reply