The scars of solitary: Albert Woodfox on freedom after 44 years in a concrete cell

Woodfox was a member of the Angola 3, a group of men wrongfully accused of murder. Now he marks the fifth anniversary of his freedom

Woodfox was a member of the Angola 3, a group of men wrongfully accused of murder. Now he marks the fifth anniversary of his freedom

Every morning for almost 44 years, Albert Woodfox would awake in his 6ft by 9ft concrete cell and brace himself for the day ahead. He was America’s longest-serving solitary confinement prisoner, and each day stretched before him identical to the one before.

Did he have the strength, he would ask himself, to endure the torture of his prolonged isolation? Or might this be the day when he would finally lose his mind and, like so many others on the tier, suddenly start screaming and never stop?

On Friday, Woodfox will wake up in a much better place. He will find himself in his three-bedroom home in New Orleans, the city of his birth. There will be colourful pictures on the wall, books to read, not an inch of brutal concrete in sight. It will be soothingly quiet – no cries and howls bouncing off the walls, no metal doors clanging. Once up, he can step outside and look up at the open sky, a pleasure withheld from him for almost half a century.

It will be a good day. Today he will celebrate his 74th birthday. Today he will mark the fifth anniversary of his freedom.

•••

On 19 February 2016, on his 69th birthday, Woodfox walked free from prison after more than 43 years inside. Almost all that time he spent in solitary confinement, on a life sentence for a murder which he did not commit.

His experiences as a former Black Panther in Angola, Louisiana’s notorious state penitentiary and the largest maximum-security prison in the US, tested his mental fortitude to the limit and beyond. It made him dig deep into reserves of compassion and resilience he never knew he had, and forced him to learn how to live in the absence of human touch.

Five years on from his release, he might chuckle a little to himself at the irony of today. This may be his birthday and the anniversary of his freedom, but he will spend the day in physical isolation along with most Americans who, courtesy of Covid, have spent the past year getting a tiny taste of what life in solitary really means.

“Who would have thought that all those years in solitary would have prepared me for living through this pandemic?” Woodfox said when we meet on Zoom. “People always want to know what it’s like. I used to tell them, ‘Why don’t you spend 24 hours in your bathroom and find out for yourself.’ Well, that’s no longer necessary – this pandemic has forced everyone to isolate and they are freaking out!”

A handout image shows Woodfox, right, being accompanied by his brother Michel Mable, left, as he walks out of the West Feliciana parish detention center on 19 February 2016. Photograph: Billy Sothern (Attorney for Albert Woodfox)/EPA

•••

One of Woodfox’s techniques for surviving years alone in a 6ft by 9ft cell was to compose a list of what he would do were he to be set free. Most of the list’s items were strikingly mundane: he would have dinner with his family, drive a car, go to the store, have a holiday, eat some good old home-cooking.

Other desires were more substantive. He would get to know his daughter Brenda, whom he’d had when he was 16 but hardly knew. He would go to the grave of his mama, Ruby Edwards Mable, who died while he was behind bars. And he would visit Yosemite national park in California, which he had fallen in love with watching National Geographic on his cell TV.

Over the past five years, he has ticked every single item on his list. A day after he walked free in 2016, he went to Ruby’s grave and told her: “I’m free now. I love you.” He has forged a strong bond with his daughter and her children. His brother Michael, a master chef by trade, comes regularly to his house to cook him stuffed crab, hot sausage or his favourite, smothered potatoes. He’s even adopted a stray dog he came across out by Lake Pontchartrain. He named him Hobo.

Not all of it has been easy. In the early days of his release, Woodfox had to retrain his body to do things it hadn’t done for decades, like walking up and down stairs or sitting without shackles and leg irons. There have been a lot of first-time experiences that were both exciting and scary: first flight on a plane, first visit to a university to speak about solitary confinement, and the one we all share – first time on Zoom.

He was anxious for quite a while about how he would fare in the outside world. He had been separated so long from his family, and he was apprehensive too about his childhood neighborhood of Tremé, which as a teenager he had plagued with acts of petty crime and fighting. “I went into prison as a kid and emerged almost 70, this patriarchal figure. So how do you fit in? When I left society, my daughter was a baby; now she’s a grown woman with three kids and four grandkids and great-grandkids beneath. And the community. When I left Tremé I was a predator on my own people. How could I make amends?”

To his relief, both sides have worked out fine. He is a present and much-loved grandfather and great-grandfather, pandemic notwithstanding. Through childhood friends, he attended meetings with community groups and apologized for what he had done back in the 1960s, asking for forgiveness. “They gave me a second chance, and since that time I’ve been working hard to earn the trust they put in me,” he said.

Some of the hardest things have been the least expected. He has felt a disturbing disconnect between the world as he knew it from his prison cell – all mediated for him through TV, books and magazines that he fought hard for years to be allowed access to – and the actual physical world that now accosts him in all its raw, unfiltered splendour.

He did make that longed-for trip to Yosemite, and almost wished he hadn’t.

“It was far rougher than I thought it would be. We went to this waterfall way up the side of the mountain. It was quite a task getting there, going up, up and up. The waterfall was so high there’s a massive spray where the water hits the rocks, and as I turned into it, it was like someone had thrown a bucket of ice-cold water on me. It was a wonderful experience, in hindsight, but in the moment, I was, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ In the cell it looked so magnificent, but when I got there I realized, you know, this is real.”

•••

Numerous scientific studies have found that when human beings are cooped up in isolation, the experience can cause psychological damage that can be irreversible or even fatal. It can induce panic, depression, hallucinations, self-harming and suicide and should not extend under international rules set by the UN beyond 15 days.

Woodfox endured not 15, but 15,000 days in solitary.

He was held on the tier known as “closed cell restricted”, or CCR, where prisoners were locked up alone for at least 23 hours a day. He went into CCR in April 1972, aged 25, and remained in it almost without pause until his release aged 69 in 2016.

Ostensibly, the punishment was meted out to Woodfox and his fellow member of a group of solitary prisoners who became known as the Angola 3, Herman Wallace, after they were accused and convicted of murdering a prison guard, Brent Miller. A mass of documentation gathered over years by his tireless defense lawyers points to them having been framed.

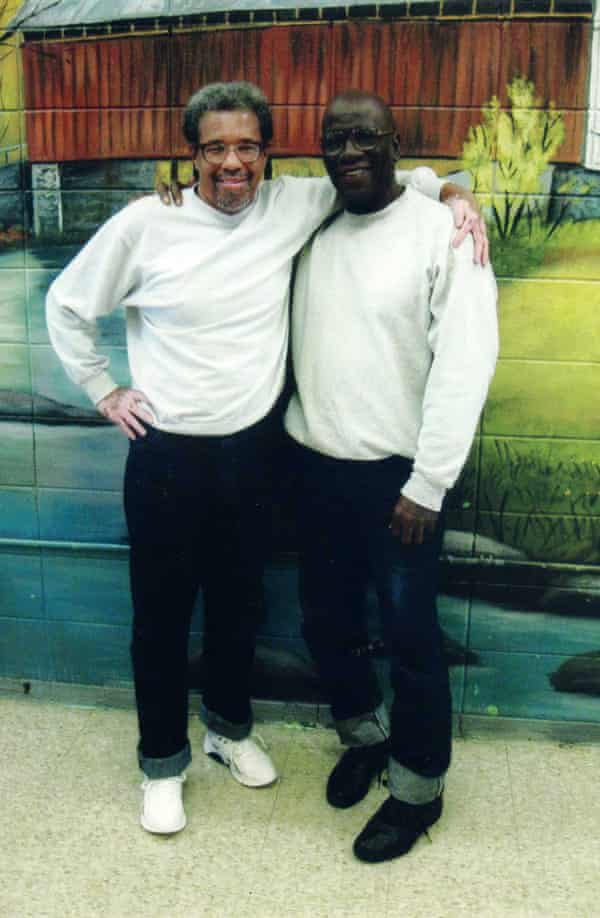

A handout image shows Woodfox, left, and Herman Wallace, right, both members of the so-called ‘Angola 3’ incarcerated at the Louisiana state penitentiary in connection with the killing of a guard at the prison in 1972. Photograph: angola3.org/EPA

There was ample forensic evidence at the scene of the murder, including a bloody fingerprint, yet none of it implicated Woodfox and Wallace. Both men, who were serving separate sentences for robbery at the time, had alibis. It emerged after the trial that the main state witness against them, a fellow prisoner, had been paid for his testimony in cigarettes and promises of a reduced sentence.

Despite all that, and many other discrepancies, all-white juries took less than an hour to convict both men in separate trials.

There is also an abundance of evidence that supports the real reason why the pair – later joined by the third member of the Angola 3, Robert King – were held for so long in the harshest form of captivity. Three years before they were framed for Miller’s death, Woodfox and Wallace set up an Angola prison branch of the Black Panther party.

They saw it as a way to fight for racial justice in an environment in which none existed. Angola was built on the site of an old cotton plantation where slaves were bred and put to work in the fields. The location was named after the African country that supplied most of the slaves.

In 1971, when Woodfox formed the Panther chapter, the prison continued to operate a system of slave labour in all but name. Black prisoners, segregated from white inmates, were sent out into the baking sun to pick cotton for two cents an hour.

When Miller was stabbed to death and culprits needed to be rounded up swiftly, the Black Panther troublemakers were a convenient target. They were thrown into solitary where they remained, year after year, decade after decade, long after the Black Panther party itself had ceased to exist. Many years into their time in CCR, the warden of Angola admitted under oath in legal depositions that they were being held in CCR because of their “Pantherism”.

If the Angola authorities thought that they could break Woodfox on the rack of solitary confinement, they hadn’t counted on his powers of resistance. And they hadn’t factored in the principles and values instilled within him by the Black Panther movement, which he says literally saved his life.

“The Panthers gave me a sense of self-worth, that I did have something to offer to humanity,” he said. “More than anything, it made me realise that the person I had become was not determined by me, but by the institutional racism of this country. My life had been set in survival mode.”

Woodfox came to believe that he could change his own destiny by simple force of willpower. “Everything solitary does to you, we managed to survive it. Not just to survive, but prosper as human beings. I wasn’t sure whether I would ever be physically free, but I knew that I could become mentally and emotionally free.”

In his 2019 book Solitary, a finalist for the Pulitzer prize, Woodfox describes how he managed to stay sane. He immersed himself in prison library books by Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey. He studied law for his appeals. He organised maths tests and spelling bees, played chess and checkers, shouting quiz questions and board moves through the bars of his cell to fellow solitary prisoners down the tier.

His proudest achievement was teaching another inmate to read.

“Our cells were meant to be death chambers but we turned them into schools, into debate halls,” Woodfox told me. “We used the time to develop the tools that we needed to survive, to be part of society and humanity rather than becoming bitter and angry and consumed by a thirst for revenge.”

The evident pride in his voice about how he had refused to be broken prompted me to ask a perverse question. Did he miss anything about Angola?

He replied without hesitation. “Yeah. I miss the time that I had. One day it dawned on me: I just don’t have the time that I used to in prison. In solitary, I had 24/7 to do what I wanted. I had structure, a program. In society there are so many more distractions, so many more demands made on you. In Angola, in the cell, I didn’t have a choice.”

•••

Albert Woodfox may have survived 43 years in solitary, but it came at a price. Over the past five years, he has observed in himself the long-term damage inflicted by conditions that the UN has denounced as psychological torture.

“Sometimes I wake up and I’m not aware where I’m at. I’m confused for seconds or minutes. I’m used to waking up seeing concrete and bars, not pictures on the wall, and for a moment it’s like, ‘Where the hell am I?’”

Claustrophobia was something he wrestled with throughout his four decades in solitary. At times, he would sleep sitting up to try to fend off the sensation of the cell walls bearing down on him.

He still has claustrophobic attacks every few months or so. Once he was in the bleachers at a sports stadium watching his great-niece and nephew compete when he started having telltale signs. “We were sitting there and all of a sudden I felt I was being smothered, like the atmosphere closing in, pushing down on me. I went outside and just walked and walked. That was a surprise – I didn’t know you could be in a stadium with a couple of thousand people and it happen to you.”

His awareness of the scars he still keeps him eager to fight for change, as he has throughout the past five years. He helped found a non-profit, Louisiana Stop Solitary, to press for reform in Angola and other state prisons. It’s a long struggle. Last year Louisiana banned the use of solitary confinement for pregnant women, the first reform in the state’s use of the practice in more than a century. But the state continues to rank No 1 in the solitary league table, with rates that are four times the national average.

Woodfox has taken his message around the globe, traveling extensively across North America and Europe with King by his side (Herman Wallace died of cancer in 2013, two days after the authorities begrudgingly let him out). Woodfox uses the power of his story to press for an end to solitary confinement, which nationally still holds 80,000 US prisoners in its brutal grip.

Last October, he became a central character in 12 Questions, the album by Fraser T Smith in which the super-producer enlists artists and activists to help him explore critical issues of our time.

Smith asked Woodfox a simple question: “What’s the cost of freedom?” The resulting conversation, according to Smith, was “life-changing”.

Smith told the Guardian he came away from the encounter with the overwhelming sense that “Albert did become free in that 6ft by 9ft cell. To hear someone who has actually lived it tell you that no matter horrendous your external situation, you can be free in your mind – that was mind-blowing for me.”

•••

In his book, Woodfox writes that he “had the wisdom to know that bitterness and anger are destructive. I was dedicated to building things, not tearing them down.”

And now that he’s out, what does he make of the political turmoil engulfing the US?

“I’m more optimistic than I’ve ever been. I’m 74, so I’ve seen a lot of upheaval in this country, and the Capitol insurrection was a defining moment in American society. It’s made people realise that democracy is fragile, it can be destroyed, that it’s only as strong as those who believe in it.”

When Woodfox first emerged from captivity five years ago, he was amazed by the number of Confederate flags he saw stuck on windows or on car license plates. It took him about three weeks, he said, to appreciate that the apparent improvements in America’s approach to race since he had been in prison were purely cosmetic.

“I came to see that America was still a very racist country. It had become coded – I guess you could say racism had put on a suit and tie. But it was still there. Donald Trump was making it safe to be a racist.”

So where does all that optimism come from? It comes in part, he explained, from the Black Panthers’ manifesto. The party may not exist any more, but Woodfox still holds tight to its values: “We want an immediate end to police brutality”, “We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings”, “We want education that teaches our role in present-day society”.

There is an unmistakable echo with Black Lives Matter, the second source of Woodfox’s optimism. “The sacrifice of so many black men and women and young kids in this country has made Black Lives Matter a rallying cry throughout the world,” he said.

In the end, Woodfox’s meditations on isolation, resilience and the cost of freedom always bring him back to something more personal. Or someone: his mother Ruby. She may not have been able to read or write, but over the years he has come to know her as his “true hero”.

The closest he ever came to cracking in solitary, to starting to scream and never stopping, was when the Angola prison authorities refused to let him attend her funeral in 1994. As he looks back today on his five years as a free man, and the 43 years in a concrete cell that preceded them, he finds himself thinking more and more about her.

“You start remembering things, things she said, how she said them. My mom was functionally illiterate, but I never saw them break her, I never saw a look of defeat in her face no matter how hard things got. I grew into my mother’s wisdom. I carry it within me.”

Leave a Reply