A review of a review: Joining the conversation with Petronella and Butch on Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and the Role of White Women in Struggle, by Veronica L.

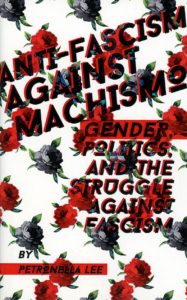

available from leftwingbooks.net see also: On Reading Petronella Lee’s Anti-Fascism Against Machismo: gender politics and the struggle against fascism (Review by Butch Lee)

I finally got a chance to sit down and study both of your texts. I read them both when they first came out, but I hadn’t read them both together. I also managed to convince some comrades to talk about them with me. No men invited. We had a good conversation and I feel compelled to share some of my thoughts after reading both texts and talking about them. It is important to continue having this conversation publicly. Perhaps others will feel drawn to join in.

I will write this mostly in the singular, but obviously the ideas are not all mine. Partly because ideas are never entirely our own, partly because some of these ideas specifically came out of conversations with friends and comrades, but I am writing this text on my own. I’m also not trying to represent everyone’s opinions from those conversations. Mostly I’m trying to clarify my own thoughts.

Part I: Fascism, Anti-Fascism, what does it all mean?

First I will address our changing context. I first saw Petronella’s text published in May of 2019 and Butch’s response in December 2019. I began this response in June 2020, in the midst of a full blown uprising against the police and for Black liberation in the so-called US, after two months of intense anti-colonial struggle earlier this year that is often referred to as #ShutDownCanada. It was also our third month of the coronavirus pandemic. The city where I live had started the process of deconfinement, though people were and are still dying every day, mostly elderly people and people of colour.

Here in Quebec, the organized anti-fascists (i.e. Montreal Anti-Fascist) say that 2019 was a pretty quiet year for the far-right. This doesn’t determine the future, but it is worth noting. So far, 2020 has also been relatively uneventful for them. Despite sections of the far-right movement declining, there remains a high level of far-right power in government. As Montreal Anti-Fascist put it, “The decline in activity on Québec’s far-right doesn’t signal a victory for anti-fascist forces. To the contrary, with a majority populist government in the Assemblée Nationale, a government that moved rapidly in its first year in power to pass the racist Bill 21 (“an Act Respecting Laicity”) on state secularism, as well as gagging debate to adopt a variety of anti-immigrant measures, it is reasonable to postulate that the right-wing forces are simply taking a breather, because they feel they’ve achieved some of their main goals.[2]”.

In the year or two immediately after Trump was elected, anti-fascism became a main way that new people were becoming politicized, even in so-called Canada. The kind of anti-fascism that was animating those political changes in people then isn’t as much at the forefront now. These days, people are being politicized through participation and as witnesses to the movement for Black liberation and struggles against the police. People of the far-right attack these protests (or sometimes participate in them), but, in the most publicized places, these far-right elements are not a main focus of the fight.[3] This shift in context animates how I’m thinking about this conversation around what fascism and anti-fascism mean.

Butch’s text raises the question, where do we take our definition of anti-fascism from? This reads as a spin off of who defines anti-fascism? For Butch, it is the original Black Panther Party (BPP). I get the sense that for Petronella, it is the BPP and also the Anti-Racist Action networks from the 90s – the punks and skinheads who were beating up Nazis across the US and Canada. It is from this history that we see a more specific definition of anti-fascism take hold. It is at least the recognition of certain tactics that we have seen dominate the popular understanding of anti-fascism in the last 5 years – beating up Nazis, “no platforming” (i.e., getting events and other publicly visible events featuring the far-right and their cronies canceled), doxxing, and counter-protests. Butch takes issue with this way of defining anti-fascism. She has a point; when we understand anti-fascism by strictly these tactics, we change how we approach the fight. The tactics will inform who we target more than any other factor, which then limits the struggle itself. Both Butch and Petronella argue this in different ways.

Petronella calls for a distinction between various far-right groups and actors so that we may pose different strategies for dealing with each of them, but the need is also more grave than that. However, this is an undeniably useful call, given the past five years of street fights between the far-right and anti-fascists at demonstrations that has preceded our current situation. The rebellion that has arisen in the wake of George Floyd’s murder has involved a wide range of tactics from burning down a police precinct to widespread looting to large day time demonstrations in hundreds of cities to negotiations with city councils and school boards. There is obviously a lot of disagreement about tactics happening within the movement and the disagreement I am most interested here is about white people participating in and, at times, “instigating” riots. This conversation is being undeniably influenced by the four years of spectacular physical violence between anti-fascists and fascists in the streets of the so-called US.

In the first few weeks of the uprising, there were unprecedented occurrences of white people calling on each other to “shut down” white rioters who are “instigating”[4]. This has lead to instances of white people beating up other white people during demonstrations[5], which is new to me, as well as white people being handed over to the police in demos[6], which is not new. I attribute this first phenomenon in part to the normalization of the spectacle of anti-fascists beating up Nazis in the streets over the past four years. This in addition to a glaring and unanswered question that we have inherited from movements past – what role do white people have to play in an anti-racist struggle? This larger question is intimately related to questions about distinguishing between various far-right groups and actors. Nevertheless, it does seem like Petronella and Butch are using different understandings of anti-fascism in order to achieve different ends. And both those definitions are useful if we are to fully understand what we’re up against.

If that’s anti-fascism, then what is fascism? Central question here. One that Butch presses Petronella on, asking us to push back against “the belief that fascism is only a shockingly unusual political happening”[7]. On the surface, I don’t think Petronella would disagree and neither do I. I see the use of being clear about the overlap between fascism and white supremacy. I even see the rhetorical strategy of using this word to describe the normal state of things under anti-Black, settler colonial, patriarchal, and capitalist realities on this continent. But Petronella’s instincts of wanting to distinguish between different kinds of fascism is helpful, if only to figure out our specific strategies against variant parts of the far-right movement and then expand this to include different strategies against the liberal power structure that is always related to fascism in our context.

White supremacists and the state itself share many goals and some tactics. The most basic interaction of the two, seen when the state plays cheerleader to white supremacist mobs (or when the police literally help far-right groups avoid arrest[8]), helps us to think about the ways in which these tactics and roles shift over time. Rather than treating Butch and Petronella’s definitions of fascism as competing definitions, we can hold both an analysis of fascism developed at a time when the state and far-right were basically indistinguishable (as Butch does), and another at a moment when the state was taking care to distance itself from the ‘fringe’ (as Petronella does). This is useful in thinking through these interconnections, and the accompanying broadening of tactics Petronella is calling for.

It makes sense that Petronella swings back and forth between identifying the bedrock of so-called US and Canadian democracy as fascism and also calling it white supremacy. Even as she wants to take it all down. This is why parts of her text could apply to anarchism as a movement just as easily as anti-fascism. Except that in this moment, anti-fascism is much more generalized as a sentiment than anarchism (specifically because anti-fascist ideas are widely understood to be less revolutionary). Anti-fascism could be seen as a gateway to more radical politics, or at least it seemed to be working that way from 2016-2019. Hard to tell now.

So fascism and the founding white supremacist principles of the US and Canada are interrelated. One way of thinking about this is that fascists regularly pave the way for liberals to march after them, fascism pushes the boundaries that liberalism can then fill in, and the threat of fascism is used by the state and liberals to maintain power. Therefore, fascism is related to, but not the same thing as white supremacy.

There is a tendency in our political circles to say “everything is fascist” but because anti-fascism has a specific set of tactics associated with it (which Petronella is trying to expand) that claim doesn’t help to develop adequate strategies against fascists. If our movements expand the set of pointed action and strategies used to fight fascism, this could also create a more nuanced understanding of fascism. Our tactics could then grow outside the parameters set for us by our enemies.

The current uprising is figuring out how to get people involved in a widening range of ways. Mutual Aid food assistance and deliveries have flourished during the pandemic, with participants picking up food for their neighbors and other vulnerable people. These types of collaborations have translated easily into leaving out water and supplies for the people in the streets, with obvious nods to the lessons from Hong Kong on the front liners’ need for support from the back and vice versa. I heard a story about how the Winnipeg general strike in 1919 was fueled by a year of mutual aid organizing during the Spanish flu epidemic. It makes sense that uprisings come on the heels (or in the midst) of pandemics. Mutual aid and militant tactics can and should fit together. Our movements need all of it.

Part II: The Role of White Women in the Struggle to End Patriarchy, White Supremacy, and Capitalism

A main point Butch makes in her response to Petronella is that white women have an important role to play in ending “men’s white race.” (18) Though we often think of neocolonialism[9] as only applying to struggles that were explicitly seen as national liberation struggles, Butch says that neocolonialism has also affected the struggles of white women, and has also coopted white women’s struggles by creating a situation “where women are allowed to advance and fill minority roles, but only as assistants acting as though they were men within abusive capitalist patriarchal structures.” (28) She says later that women (unclear if she means explicitly white) were the first proletariat and will eventually be the last (21). Finally she writes, “what’s basic for us is that without white women and our reproductive labor, there is no white race.” (21).

What does all that mean? Many parts of the women’s liberation movement were thoroughly coopted since the 1980s by academia and the non profit industrial complex. They were undermined by the white upper middle class character of their base, which allowed the goals of the movement to morph into access to power in white men’s world for a small percentage of white women. Power structures shifted marginally to allow some token white women in positions of power, but the basic structure of things stayed the same. Butch makes clear that white women refusing to help white men reproduce the white race would effectively end the white race.

There is a tension here between different ways of understanding whiteness, which Butch sort of acknowledges in her piece. On the one hand, whiteness is something that isn’t real. It is a power structure that shifts and changes over time. It isn’t biologically set in stone. It is socially produced for specific ends. In this sense, there are some blurry edges to whiteness that make it confusing at times. Whiteness can become somewhat expandable depending on the context. On the other hand, whiteness is very material. It is a material thing that literally needs to be reproduced through the creation of white babies and the reproduction of its institutions (among them the nuclear family and marriage).

In the Military Strategy of Women and Children, Butch writes “revolutionary women’s culture begins when we leave the table” (18). Certainly leaving the table is big project. Written this way, it becomes clear that the proposal at hand is a revolutionary proposition, not just an individual action. Some white women have been refusing to do reproductive labour for a long time now and this has meant that women of colour have been forced to do it (think surrogacy, wet nurses, live in caregiver programs, etc). We must aim for bigger and more strategic ends that are more clear through their means. No more fighting for a seat at the table. More energy spent destroying the table entirely.

How do we leave the table? And who are we while we’re doing it? In the past, people have called for a revolutionary organization of white women. Butch calls for this implicitly. Amber Hollibaugh talks about lesbian separatism as a form of nationalism, which I hadn’t heard before but it makes a lot of sense[10]. The national liberation struggles of the 60s, 70s, and 80s have always resonated to me as the most recent high of revolutionary struggle in this context and there is something super compelling about trying to recreate that high. But the reality of neocolonialism means we can’t just rinse and repeat. It won’t work.

One form of leaving the table in our present era has been called autonomous organizing. The LIES collective has published the most helpful framing of this conversation that I’ve seen to date. In their piece on autonomous organizing in LIES II, they call for “a practice of autonomy built around the exclusion of cis men, rather than around a static notion of “womanhood”, a gender-essentialist and cis-supremacist notion of “female-bodied-ness,” or an insufficient and problematic notion of “lesbian separatism.”[11] They write, “So many of our current projects after all began as a kind of naming: some people getting together, finding a shared circumstance, and then finding a shared interest in approaching it with antagonism, as a start.”[12] First, don’t assume shared identities, find shared circumstances. Second, approach with antagonism, which I understand to tie in to things Petronella had to say about militancy.

This perspective focuses simply on the exclusion of cis-men, which I understand as an explicit nod to trans and queer liberation movements that have pointed out the gender binary as an institution to destroy alongside patriarchy. In some ways, this articulation of who we are has a tension embedded within it that is similar to the tension I named earlier around whiteness. Gender is at once a socially constructed category that shifts and changes over time, while also being materially concerned with our bodies themselves, how we understand them, and are understood by others, which all can have real material impacts on peoples’ lives. Obviously there will be tensions and contradictions within formations that do not include cis men, but defining who is in the room in this expansive way can produce useful collaboration across difference while bringing together those who are likely to be able to find shared antagonisms.

However, the most successful moments of autonomous organizing without men that I have tried have also built upon shared politics and affinity. These formations have used autonomous organizing without cis men to strategize the end of white supremacy, of patriarchy, of capitalism, of the settler state. They have decentered the men who were the glue between different parts of any given political landscape. These spaces with no men became ways for us to build relationships that didn’t involve those men, allowing us to carry those relationships into other organizing projects in our lives. We have cut out the literal middle men in order to give them less power. That is a step towards leaving the table.

Though I want more. I am thinking of the importance of having other reference points or movements to be in conversation with. We aim to be embedded within a constellation of revolutionary movements and groupings as one node within that. We need other movements and spaces to keep ourselves responsible and accountable. Is that happening today? Sort of? Feels closer today than it has ever felt before in my life. But the autonomous organizing without cis men in my context has not managed to carve out enough space to hold its own.

What is missing? Why hasn’t this happened more? Are people without the determination to do it? The willingness to take the risks associated with it? A lack of answers (and perhaps, disagreements) to questions around what kind of formation is up for the task? Enough clarity around what it is that we are even trying to do in the broader sense? Probably all of the above.

One block that comes up in relation to Butch’s text specifically is about land and the material ability to carve out autonomous space. Butch wrote “The 1960s feminist awakening talked about women needing our own material territory. Our ‘space.’ Whether it was Ginny Woolf’s ‘a room of one’s own’ or a college department of our own. Or lesbian land or the ‘Michigan’ festival. How is this different at the root from what Rez traditionals or Black nationalists build?” It seems like she’s asking this question rhetorically, but I want to find some answers. How is it different for autonomous organizing that excludes men to “need our own material territory?” Does that mean having a land base? Does that mean owning land? If that organizing is mostly made up of white women[13], what are the implications of that in an anti-Black settler state that has from its beginning involved white women enforcing its hierarchies and advancing its settlement?

We have to seriously think about this question around land and space. Given the history of much of the so called US and Canada, there are ways of white people relating to land that are thoroughly colonial (buying it, inheriting it, relating to it as property, even squatting isn’t inherently anti-colonial in this context given the history of white people squatting Native land here). There are ways that relating to land is totally contextual on social position (i.e., the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Africa’s relationship to what is now the Southeastern US has liberatory potential in ways that Cascadia doesn’t). I am also thinking here about Indigenous sovereignty as well as the basic idea of land as relation that I understand to come out of Indigenous movements and cultures. There is the reality that this is a conversation to be had between movements and one of the movements in the conversation doesn’t exist. Indigenous movements and Black liberation movements are seeing a resurgence today, so we can see what’s missing. #MeToo isn’t cutting it[14].

How do we bring it into being? How do we build a movement without men that is committed to an expansive understanding of anti-fascism and that embraces feminist militancy? How do we do that while avoiding the missteps of the past? There are lots of different answers to try. Luckily we’re in a moment when many people are feeling newly activated against the police and for Black liberation. It is the perfect moment to start a renewed push to bring this movement about and see what a new generation has to say about these questions.

Veronica L. is a white cis woman who lives in so-called Montreal.

Notes

[1] For those who don’t know, #ShutDownCanada was a hashtag that came in the wake of yet another police raid on Wet’suwet’en territory in so-called British Columbia. Wet’suwet’en people have been blocking the path of a pipeline for more than a decade and in the past two years have faced two rounds of brutal raids and subsequent solidarity actions across the country. January 2020 was no different. In the wake of the raid, Kanien?kehá?ka people in so-called Ontario and Quebec blocked railroad tracks in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en people and the tactic spread widely. By the end of February there had been dozens of rail blockades, some lasting days, some lasting weeks.

[2] Between National Populism and Neofascism: The State of the Far-Right in Québec in 2019

[3]Obviously there is a lot of overlap between the far-right and the uniformed police. However, most cities where these demonstrations are happening like to maintain at least the illusion that there is a separation and in some circumstances will penalize individual officers who are caught participating in far-right movements.

[4]This tweet in particular went viral: https://twitter.com/LouisatheLast/status/1266737893118300160. The comments are instructive on how people were interpreting “shut down”. Here it is “removed if they don’t immediately back down” https://twitter.com/donnafullhart/status/1266954838811779073?s=20.

[5]Here is a video of a white guy chasing and tackling another white guy who tried to break a window w the tweeter cheering it on https://twitter.com/queencitynerve/status/1266940913361850369?s=20.

[6]Here is a video of a white guy breaking up paving stones with a hammer getting tackled and kicked by white guys, but handed over to the cops by what appears to be a mixed race group https://twitter.com/s_Allahverdi/status/1267240521052946432. Handing fellow demonstrators over to the police was a not-as-uncommon-as-it-should-be tactic used during the 2012 student strike by people who became colloquially known as the paci-flics, a combination of the word pacifist and flic (cop).

[7]Page 16 of the zine version, https://kersplebedeb.com/posts/on-reading-petronella-lees-anti-fascism-against-machismo-gender-politics-and-the-struggle-against-fascism-review-by-butch-lee/ – all other quotes from Butch are from this text unless otherwise specified

[8]One well publicized example here: https://www.irehr.org/2020/06/18/three-percenters-pose-with-olympia-police-officer-sparks-need-for-thorough-investigation/

[9]Butch describes neocolonialism as “where [western imperialism] pretended to honor the political independence of former colonial nations and peoples of the capitalist periphery. But kept indirectly feeding on them behind the scenes… Working through bribed native political leaders, military dictatorships, and dependent local capitalist classes.” p20

[10]Amber Hollibaugh, My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home

[11]Page 59, LIES II “To Make Many Lines, to Form Many Bonds”. They also point out that this practice of autonomy can also be used for other categories, for instance excluding white people.

[12]Page 58, same text

[13]I’m taking it for granted here that autonomous organizing only makes sense when excluding categories of people who have access to power over other groups of people, so autonomous organizing that excludes cis people or white people makes total sense to me, while autonomous organizing that excludes trans people or people of colour makes no sense to me and, in fact, feels fashy. Didn’t feel like this needed to be said cause it feels like common sense, but saying it here anyways. In this sentence specifically I’m also assuming that an autonomous space without men in my context would likely involve a lot of white women even if there were no (and shouldn’t be any) intention to keep non white non men away from the project.

[14]As I finish writing this text, #DisSonNom has taken off in Quebec. It is a giant public call out of sexual violence in the “progressive community” that I do not feel like I know enough about to even sum up correctly. The mainstream media is calling it a movement. There is a first demonstration happening this weekend. I feel a mixture of hopeful and skeptical but need to do more research and give it more time before having a sense of what is happening.

Leave a Reply