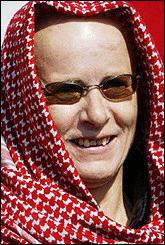

Joelle Aubron (ex-Action Directe member and political prisoner) Interview

An Interview with Joelle Aubron

Born in 1959, Joelle Aubron is a former Action Directe political prisoner. Action Directe (AD) was a communist guerilla organization active in France in the 1980s. AD grew out of the French autonomist scene, drew heavy inspiration from both the struggles of the Third World proletariat and the intellectual legacy of the new communist currents of the 1960s and 70s. It carried out a number of spectacular attacks, many of which were in cooperation with Germany’s Red Army Faction. Aubron was arrested in February 1987, along with fellow Action Directe members Jean-Marc Rouillan and Natalie Menignon.

On June 16th 2004, at the age of 44, Aubron was released from prison on health grounds – she is suffering from cancer. (According to French law, those suffering terminal illnesses can be released to die at home.) “The liberation of my comrades is a battle still being waged,” she said, as she left the prison.

This interview was carried out by the anarcho-punk webzine Future Noir over the period 2002-2003. It was translated from French to English by Kersplebedeb. Footnotes are from the original, except for those in square brackets, which are provided by Kersplebedeb for the sake of context.

Those interested in reading more by the comrades from Action Directe are encouraged to check out the pamphlet Resistance Is A Duty! and other essays by comrades from Action Directe available from LeftWingBooks.net.

INTERVIEW WITH JOELLE AUBRON of ACTION DIRECTE

1) How was AD structured? Was it just one section that was devoted to armed struggle or was AD an armed organization plain and simple?

AD did not have legal and armed sections, any more than it was represented by a political party. Political and military unity was a necessary precondition to guerilla action. It is no simple matter to explain everything that led to this unity.

We did not start out from point A in order to reach point B. There were many factors that led us to take up the strategic weapon of armed struggle, to apply it in the imperialist metropoles,1 and it was not a linear progression. The activity of the guerilla on this continent did not consist of a pre-planned method. There was no rulebook telling us how to do it.

We inherited the past and invented the present in an explosive mixture of breaks and continuities. The easiest thing would be to give an example with a key concept: workers’ autonomy.

The question of workers’ autonomy, as a class for itself and also as a movement to abolish all classes, is at the heart of communist history. And within this movement to abolish the existing order, to abolish classes, I include those anarchists who also demand this emancipation. From the Paris Commune to contemporary struggles, the form and the appearance of this autonomous class action are themselves at the heart of the disagreements between communists and anarchists.

And yet, I’m sure most people who grasped the new possibilities of the sixties did not do so as a result of studying some book. This approach and historical awareness was “naturally” available in the atmosphere of those times. We were rooted in history. Within the French State, from the Maoists to LIP2 to the struggles of immigrant workers, this autonomy was not limited to the autonomist movement of the late seventies. As a result of the sixties, the idea of the Communist Party being the vanguard once and for all, as it had been understood since 1917, was largely discredited. But it was not a matter of liquidation and conversion to anarchist ideas. It was first and foremost a process, practices, confrontations, experiments, new horizons.

It was a matter of what had happened to the Communist Parties that had come out of the Third International; their inability to deal with many of the aspects of class struggle that they had seen developing since 1945, specifically in regards to the national liberation struggles.3 But it was just as much a matter of the return of a section of the ex-“New Left”. After having distanced themselves from the old Communist Parties, the far left parties played at being Iznogoud wanting to replace the Caliph.4 By the end of the seventies in Europe we were witnessing the farce of their umpteenth ideological conquest of the masses, their quantitative gains in their electoral carnivals, their keeping struggles contained within the proper institutional channels. Realizing what a farce this was combined with other realizations.

One of these other things we realized was the role of institutional social controls. This was not new; it was not really any different from the insurrectionary position which criticized the idea that there would be a slow accumulation of forces within ideological debates and trade union work. As early as the 1930s, Gramsci had identified the need for a new strategy to overcome the preventive counter-revolutionary5 institutions that the bourgeoisie was developing to keep its monopoly of power.

But this need was also something that was accessible “in the air” of the times. Subversion was everywhere, turning everything into an opportunity for critical action and visions of how radically different things could be. Daily activism consisted of occupations, violent demonstrations, traditional activist mobilizations but also attacks and expropriations. This produced a political situation in which revolutionary politics advanced on two feet: the movement and the guerilla. It was action born of the realization that a new kind of vanguard was needed in order to effectively “overthrow all relationships that degrade, submit, subjugate, and destroy men and women.”6

Realizations and facts that created dynamics which in turn opened up a number of possibilities. “Our only real strength lies in the unity of comrades in the factories, in the neighbourhoods, in the schools, in the offices; a unity without insignia or membership cards, refusing all divisions that threaten our true class unity; in other words, the revolutionary strategy. From this unity comes the proletarian left, and only the proletarian left can build, through struggle, the revolutionary organization.” (Sinistra Proleraria, 19707). The words and expressions were related to concrete situations, they were based in reality. Our inspiration came from the classics, from Marx, Engels, Lenin… but we also drew from Mao, Guevara and Frantz Fanon. Marxist theory and the new theoretical advances coming out of the national liberation struggles combined with and confronted each other. We drew on the Situationists just before ’68 and we used Althusser to strengthen our analysis. This wasn’t just an intellectual hobby. Taken by the ideas in a pamphlet, arguments fiercely defended in a meeting, our references were made real in our practice.

And so it was from this happy mess that the practice of armed struggle on this continent emerged – albeit with often major differences from one guerilla group to another. A strategy of proletarian unity which implied a break with institutional social controls.

Awareness of these controls was practically at the heart of this option. And it was with Althusser that we unraveled how these structures relate to each other: the economic base, the social and human relationships which it produces, the State and the social and class bodies that it “autonomously” creates, the political and cultural institutions and their impact on our lives, how they represent us and our imaginations.

At this point, the situation at the end of the sixties made it painfully obvious to what point things were contaminated by the preventive counter-revolution. Practically everywhere around the world the working class’s political and trade union organizations had abandoned their tasks. Of course, it wasn’t the first time this had happened, for example in 1914 the social-democratic parties had smashed the Second International on the alter of the bloodbath that was the First World War. Nevertheless, what was new was the existence of the guerilla option. This essentially came from the post-WW2 liberation struggles in the three continents.8

Armed struggle – which had become a strategic tool of revolutionary counter-violence – was the answer to the counter-revolutionary policies, to all the institutions, to the collaboration of trade union and political organizations. We took the idea of “protracted revolutionary warfare” from Mao and we adapted it to our metropolitan realities. We gave up on the idea that a gradual accumulation of forces should precede armed struggle “when the time is right” and instead made guerilla activity an indispensable tool of revolutionary class war right now, something that could destroy the system of global exploitation and build an alternative social organization.

As opposed to waiting, to sending yet more delegations off to Vietnam, guerilla activity elaborated a strong connection between the struggle today, the critique/breaking point and the goal. Preparing revolutionary warfare and insurrection is itself a politico-military activity. It is the war of resistance, the counter-violence of revolutionaries confronting the brutality of the exploitative and oppressive system.

After Genoa, I heard a demonstrator say to the media that “violence is burying the future.” This kind of formula doesn’t mean anything, except maybe that one is brain-dead. The system’s own violence is seen as natural and under control. Even though all societies may try to claim that violence is an external problem, and may develop different rituals – sometimes themselves very violent – in order to keep it out, in the present situation where 358 personal fortunes greater than one billion dollars represent the equivalent annual income of 45% of the world population, that is to say 2,3 billion people, more than ever one has to refer back to the semantic difference Genet underlined in 1977 between “violence” and “brutality”.9

This example alone exposes the alienating procedure in which the spectacle of protest is trapped. The basic facts of who has the power are denied, erased from the picture. The ability to perceive reality is blocked by words whose meaning has been lost. The concrete conditions of the system’s structural brutality are – at most – condemned, but not fought against.

The ATTAC10 and other citizens’ groups pretend to be renewing the content of formal democracy, such as it developed since the 19th century. Yet regardless of what social or political rights may have been won as a result of very bitter struggles within the framework of that idea, the relationship between capital, labour and the State, the framework and the rules of that “democracy”, are already the result of the capitalist mode of production in all its vampiric glory, sucking the blood of subject labour. By the 19th century this vampire had already pretty much achieved in Europe the “expropriation of the mass of the people from the soil [that] forms the basis of the capitalist mode of production.” [Capital, Vol. 1, Part VIII, Chapter 33]. It then set out to conquer other worlds where wage-labour was not yet the form of social relations of production. Now, at the beginning of the 21st century, the vampire is still living on the workers’ blood by two arteries: the one where it pumps the blood of workers in the metropoles and the other one.

And yet this unity of the political and the military in no way meant that we saw violence as the “motor force of history”. On the contrary, faced with the institutionalized, peaceful violence of the relationship between capital and labour, the foundation of class society, we felt that counter-violence would be a way of reclaiming moments of power for and with the oppressed.

At the end of the sixties the bourgeoisie was faced with a crisis of domination, a crisis of the model of accumulation and of capitalist social relations, and this raised the question of the oppressed taking power in a particularly sharp way. At the same time, within the same movement, ideas of proletarian internationalism and anti-imperialism were also being completely renewed.

2) What was the relationship between Action Directe and the Red Army Faction?

The January 1985 joint text was the result of objective conditions, of experiences and discussions. And also because revolutionary politics was advancing on two feet – the movement and the guerilla – the experiences and analyses were being discussed between the different components – the guerilla itself, resistance groups, and groups organized around more specific questions.

No matter what some idiots might have claimed, this text never spoke of a merger of our two organizations. Not only did we keep our own names as well as our own organizational structures, but if we officially decided our politico-military campaigns together this meant that there was an ongoing discussion. “This project, as an open process aiming at joint action, should smash the centers of imperialist strategy because it is here that they must build themselves up economically and militarily in order to maintain their global domination.” (AD-RAF Joint Statement, 1985)

With the RAF, and also earlier with the Comunisti Organizzati per la Liberazione Proletaria,11 we went beyond simply helping each other out occasionally as a form of active solidarity, which was nothing unusual at the time. It was no longer a question of just sharing explosives, guns, false IDs and money or even of helping each other out with logistics. We were now attacking together.

In September 1988, at the opening of the bi-annual meeting of the World Bank and the IMF in Berlin, the RAF attacked Hans Tietmeyer, Secretary of State of the Federal Republic of Germany and delegate of the IMF and World Bank at world economic summits. A joint statement from the RAF and the BR/pcc [Italian Red Brigades] was attached to the communique from the Khaled Aker Commando.12 It underlines how “the historical differences in political developments and orientation… cannot and should not be an obstacle to the necessary unification of different anti-imperialist struggles and activities in a conscious attack against imperialist power.”

When discussing a process like this, there is always the risk of giving a linear description. And the worst thing about such a description is that it lends credibility to those who have repented and now regret having ever dreamed of changing the world, those who now promote submission.

Nevertheless, a chronological list should be able to give some idea of the combination of factors that allowed this step:

- the profound renewal of internationalism and anti-imperialism which was a fundamental part of the practice of armed struggle on this continent,

- The strategic statement “The Guerilla, the Resistance and the Anti-Imperialist Front”, published by the RAF in 1982. I will attach some extracts from this long text.

- The progress of the West European bloc and the consequences this reactionary development held for the proletariat and the people of the Three Continents.

These factors were not just added together to give a programmatic model. They were inter-related, interacting with each other and with a host of different practices. And it was all of this that together confronted the bourgeois backlash.

Between 1979, when AD first made its appearance, and 1982, the balance of power had already shifted, and not in our side’s favour. Without being able to go into all of the different factors which played a part in this change, I will simply state the end result: the bourgeoisie was on the offensive again. War was declared on the people of the Three Continents, the new imperialist strategy was clear at the “Versailles Summit” of the G7. A few weeks later, the State of Israel launched “Operation Freedom for Galilee”, invading Lebanon and carrying out massacres in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.13

In the same way today everyone can see the connection between an unabashed imperialism under the pretext of a “war against terrorism” and the Sharon government’s attempt to finish off the Palestinian people once and for all. And every oppressed people can see how this pretext serves the State which oppresses them. And yet, it is not only a pretext. It is clear proof of the relationship between freedom from capital and freedom from imperialism. The more the capitalist means of production reaches the “genetic” limits of its mode of development, the more brutal are its imperialist consequences.

The relationship between these two freedoms was always central to AD’s strategy. In 1982, when the reality of the situation, of the way in which the balance of power was shifting, showed the outline of this relationship, we carried out the June and August campaigns: a strong mobilization against the Versailles Summit, many operations including a spectacular attack on the headquarters of the IMF and World Bank, attacks on Israeli and American companies including the armed occupation of the headquarters of the Chase Manhattan Bank.

And so, when faced with this situation, we still had a few cards up our sleeve. The need for a practical critique of outdated forms of internationalism showed the way for new paths of resistance. Starting from the existence of guerilla politics across Western Europe, the RAF took on a project greater than had been seen before.

But this project of a common front of the different forms of resistance was itself part of a larger process. We outlined this in a text that was published at the time of our May 1994 trial, under the title “From ‘Sympathy’ to Strategic Convergence”:

“While the European question has hardly been looked at so far, it will reveal itself in the course of the confrontation with the bourgeoisie and the forces of reaction. And it is basically within this process that one can find the beginning of the resolution […] To be a reference point for the proletariat in a process of longterm social warfare, revolutionary commitment must take into account all the realities of its age and, in the first place, the tendency of the imperialist European bourgeoisie towards integration and the weakening of the nation-state. The recomposition of the proletariat depends on being able to go beyond institutionalized politics and being able to represent the interests of the proletariat and its concrete anti-imperialist solidarity with the proletarian and oppressed peoples around the world. A process of unity based on the fundamental contradiction between the international proletariat and the imperialist bourgeoisie. Since the end of the 1970s, with the worsening crisis and the related greater tendency towards war, both strategic convergence and an awareness of the obvious limits of simply objective unity became possible….”

Seeing as the reactionary nature of the European entity is obvious to everyone today, it can seem like no big deal to refer to it this way. But when I quote what we wrote in 1994, I am quoting what we knew right from the beginning of the 1980s. Whatever our errors and mistakes, we took this political responsibility full on. And I am proud of it.

It goes without saying that the defeat we suffered shows our limits and our errors. In retrospect, I have the impression that we, the guerilla and other initiatives for revolutionary unity in Western Europe, were miles ahead of ourselves. Sure we knew, practically speaking, the new nature of international class warfare, but we were still far too voluntarist to be politically effective. We did not realize to what extent we had entered into a defensive period for the conquered and oppressed. Very conscious of the strength of the bourgeois counter-offensive, we had a real sense of emergency, and yet we did not quite grasp all of the ramifications of this counter-offensive. Of course we saw the defeats, but we took them for unfortunate setbacks we had to move beyond.

And this is particularly true for those of us in Action Directe. The coming to power of the left after thirty years in opposition blinded us to the extent to which critical ideas and practices had regressed. We took this regression to be local and temporary.

The truth is, I am not very sure how accurate this evaluation is. We can see today how cruel the effects of this counter-offensive are, especially on the ideological and political levels, in the way in which people see the world and how they feel they can act on it. But this remains only part of the picture. The history of armed struggle on this continent has yet to be written. Those of us who have still not given up on changing the world, we cannot simply accept the ideological and political assumptions of bourgeois historiography. Especially as concerns revolutionary counter-violence.

3) Action Directe was an anti-capitalist organization, but most of your attacks were against the government. Why not target multinationals? Wouldn’t you agree that governments are just the lapdogs of capitalism?

Ouch! It is painful to hear a question like that. Amongst the tools that I use to understand reality in order to change it, there is a good dollop of Marxist theory. And so that question is painful because the relationship you seem to imply exists between multinational corporations and governments seems to me to be one of the effects of the dominant ideology, “false consciousness reflecting real conditions”.

Over the past years a certain nostalgia for the interventionist Welfare State has taken root in activist circles. To summarize quickly, the belief that the State should have the job of protecting the nation-state’s territory from the effects of “free market” competition and its dogma of profits-at-any-price. I am not going to go over the historic role of this State model, the complex relationship that there was between different factors in that period of capitalist development from, roughly, the 1930s to the 1980s. I will mention just two, which are of central importance in that their interactions can help us to understand the different levels of the socio-economic formations of that historical period:

- the development of a mode of accumulation where labour was tied to Taylorist assembly line production and the consequences for the bourgeoisie of the crisis of overproduction in the 1930s, namely what are commonly referred to as Keynesian policies where a mass supply is associated with a mass demand.

- a certain kind of class struggle which involved both the reality of the mass worker, regimented by the assembly line in the big production centres, the existence of an “alternative model”14 and, consequently, the defensive posture adopted by the bourgeoisie, at the same time as it was confronted with the national liberation struggles in the periphery.15

To continue with another example, regarding the actions from 1984 on, it is not a coincidence that before he was a specialist in mass layoffs, the great technocrat George Besse16 was in charge of important French developments in an industry where there is a direct connection between civilian and military applications; from the Pierrelate factory to enrich uranium to the treatment of waste at The Hague from which plutonium is produced. Nor was it a coincidence that Guy Brana,17 at the time the number two guy at the CNPF, spent most of his career with the transnational corporation Thomson. Nationalized in 1981, this company produced civilian and military high technology and was one of the major players in the “Public Industrial Sector”, a war machine for the bourgeois offensive going on at the time.

As in all imperialist countries, the monopolies and the State are obviously the bourgeoisie’s main agents of class struggle. But in France their fusion (the State’s monopoly capitalism) took on very specific characteristics. The State played an enormous role in the economy and in production itself, thanks to its “Public Industrial Sector”. So in the early 1980s the main weapons of restructuring were concentrated in the Mitterand State. Including the weapons the bourgeoisie needed to wage its class war, meaning to restore the rate of profit and put in place its new neo-liberal model. And it is clear today that many “left-wing” governments act this way. Most banks and lending institutions had been nationalized (36 banks, insurance companies and financial institutions), and the five main industrial groups, including those responsible for over half of all high tech production, were in the hands of the State. As well as almost all the sectors involved in new production, aeronautic and space industries, communications, pure research… and it was precisely these sectors that were used as models for the most radical restructuring, from the introduction of new productive watchwords to the total control of the workplace (work groups, zero default, zero stock, zero spare time…). It was also here that the most shameless speculation took place, such as the Credit Lyonnais and AGF scandals.18

It is from the “Public Industrial Sector”, where military production is almost ubiquitous, that the characteristics of the new business model spread to other companies, small businesses, and society as a whole. So it is the State itself that introduced the heightened level of exploitation, that pushed the capitalist extortion of labour even further to a new level.

Action Directe’s targets were involved in this State activism, in thinktanks like the OCDE where multinationals and States developed their policies, in meetings where they thought up imperialist aggressions, in military structures like the Western European Union and economic structures like the World Bank and the IMF.

One cannot accuse our organization, or the European guerilla in general, with having failed to grasp the gravity of the bourgeoisie’s counter-offensive, and the possible consequences for the international proletariat.

4) What do you think of activism today? What differences do you see, compared with what was going on at the time of Action Directe and the Red Army Faction?

When I look at activism over the past few years, it is from a very particular point of view. My perspective basically consists of two things.

First, the years in prison. My relationship with what is going on today is necessarily very intellectual. I can’t see, or hardly, the living contributions, how people actually come together in the different situations and, along with that, the connections, the emotions… in short, that collective subjectivity, an essential part of the struggle and of life. I am in a certain sense out of touch, kept in an involuntary ivory tower where what people are theorising is more important than what they are doing. Given the way in which I lived out my own politics, it is not a very comfortable place to evaluate things from.

Secondly, the “defeat” that we suffered. When I say “we”, I am referring to far more than just those Action Directe activists who are still in prison. In 1968 I turned nine years old, so I am not of the generation of ’68. Nevertheless, I started from that revolutionary surge “there”.

There were many different expressions of the strength of the desire for liberation and emancipation19 in that surge. They were present throughout the different experiences of men and women:

- The struggles, whether armed or not, in the three continents, which confronted local dictators supported by the imperialist powers, or else directly confronted the armed forces of the latter, and the struggles of the oppressed in the very heart of those imperialist powers.

- The struggle of women to act and think critically against all those institutions where human beings are molded to serve capitalist social relations and the reproduction of alienating submission…

By the end of the 1980s, this surge was “finished”. In quotation marks though. It was a defeated at the hands of a bourgeois counter-offensive that we had seen getting stronger and stronger since the 1970s. In the long war between exploiters and exploited, a battle was lost. Yet the undeniable historical break which is the cruel result of this surge ending should not be confused with being finished once and for all. It is simply a cycle of struggle which was finished.20

The 1990s, especially the first half, were a nightmare, as we fled from the naturally oppressive march of history. Our oppressors were in a position to brag.

Today, that phase is behind us, and over the past years we see the outlines of what we hope may be a new surge.

Within which there is of course what the media calls the anti-globalization movement. At first it seemed to me to be monstrously dominated by social-democratic assumptions. Nostalgia for a “social” State, demands for “better redistribution of wealth”, which don’t really question the foundations of the system. Indeed, in this way they limit the hopes of life, pull them down inexorably into the rut of reformism, all the more senseless given that the decay of this very system is characterised, amongst other things, by a deep reactionary impulse (see what I said about the ATTAC and other partisans of global citizenship). Faced with this, the more radical expressions were put on the defensive, people dusted off their prayer-books (whether communist or anarchist) in an attempt to to counter this falsified and falsifying view of reality. This was a high point in sect-like behaviour and competition between different brands in the marketplace of the protest spectacle. Over the last little while, I have the impression that things have started to get better. The opening of spaces for critical discussion and actions and all sorts of interesting things. You’ve got to admit that reality really helps us here. Especially since September 11th and the pretext that the new “holy crusaders” made of it.

Already, in light of the series of events that have transpired over the past months, it is difficult to continue to reject the analysis of imperialist relations. Globalization is the name of the new form of imperialism. In the same was that the means of accumulation changes within an “eternal” capitalist mode of production, the forms of imperialism change. On the one hand, a clearly visible pyramid with the United States sitting on top; on the other hand, the utterly reactionary nature of this relationship of forces where its pretensions of acting on the world seem to be exhausted by the very spectacle of its powerlessness. It is definitely a very dangerous situation. For at least two reasons: the impressive attack power that imperialism has developed and the temptation of miracle-solutions with their scapegoats and heaven-sent politicians.

But despite myself, despite being well aware of these dangers and what they mean for the different spaces where life and creativity exist, I am not convinced that the desire for liberation and emancipation has been destroyed. A while back I wrote a text21 about commitment where I compared it to the old myth of Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods so that men would no longer be at the mercy of their blind and arbitrary power. An insurrection where perseverance turned lost illusions into power for the future. The goal of developing liberatory relations between people is at the heart of the human adventure. Throughout the ages its ideological, political and social aspects are expressed differently, there are often mistakes made about how to realize it, but nevertheless it is always reborn from its own ashes. It is intimately tied to life, to its surging forth there where it was least expected.

I am thinking about really a lot of things that all have in common the desire to change the situation and change it concretely. In a maquiladora town close to Tijuana, faced with the desertion of the so-called public authorities from this free trade zone, the women are creating popular education initiatives, they set up as school with 300 places, and set up a university of knowledge and philosophy. Recently a Civil Mission for the Protection of the Palestinian People succeeded, through the presence of internationals, in allowing Palestinian workers to fix the water-pumps in a camp, abandoned for 15 days and under fire from Israeli snipers. A film-maker makes a film with street-children in Daker after having set things up so that his project helps the kids in the long term. I have chosen “small scale” examples, carried out in situations where death is never far away. There are countless others. Day after day, they deconstruct the destruction and the unfavourable balance of power, even if they are not enough to reverse this balance.

There are more and more people resisting around the world. For those of us who persist in fighting for the future, having experienced defeat may be an advantage. We have lived through the exhaustion, the death of an upsurge. Today, we are seeing and living the budding new life behind that phase. These situations where the invisible recreate the consciousness of being the only creative multitude, they reinvent our ability to function while asking questions.

From various things I have been reading, I am seeing things coming together. It seems that anticapitalist critiques and actions are once again taking place. After having thrown out lots of babies with their bathwater, notably in the way of concepts and grasping reality in a way that serves the oppressed, we are leaving our defensive positions. Calls that “we want it all and we want it now” can once again be heard. In any case, nothing else is possible. What I am saying here is very vague but there are so many realities where once again we can see global understandings of struggles, resistance and hope. In any case, it is going better than it was in the mid-nineties.

Of course, the brutality of the steamroller at work puts these initiatives at risk. And this vulnerability can be exacerbated by our defensive reflexes to maintain our dogmas when everything is going bad. But this is precisely why I am so happy with your next question, because you are an anarchist and I am a communist.

5) You believe the proletariat should take power. Don’t you think that it should destroy the bourgeoisie and the State to bring about a self-managed society where the proletariat would no longer be exploited and oppressed?

On the one hand, your question highlights one of the essential differences between the anarchist and communist labels. On the other hand, in the eyes of history – notably the last century – it is a caricature of it.

This forces us to return to the essence of the anti-capitalist revolutionary project, to its attempt to develop a liberation of possibilities and the emancipation of human beings. From there, we can see what opposes this effort. I am going to have to refer to Marxist categories but, well, there are anarchists who use them too, so I hope that this will make them more palatable to you. So according to a Marxist analysis, there are two contradictions from which almost everything22 follows:

- capital / labour;

- development of productive forces / private appropriation of socially produced wealth.

They are in any case the basis of the proposition that the exploited and oppressed class, having nothing to lose but its chains, has the historic mission to abolish all classes.

It is only following this that we develop different proposals to realize this “historic mission”, And amongst these proposals, the split between anarchists and communists regarding organization. What is the means by which the class can accomplish this mission? What tools should it use in this struggle? And, when there is a revolutionary upsurge, what structures will allow it to go even further in tearing apart that which oppresses, and in building that which liberates? It is around these questions and experiments that two questions arise:

- To conquer State power or to destroy it

- “Democratic centralism” or “federalism”

As far as I am concerned, neither the communist nor the anarchist experiments have produced a model that can simply be referred back to for an answer. Furthermore, the current absence of a revolutionary surge makes me even more wary of the temptation of programmes based on what might have been if…

- …according to the Trotskyists, if the Stalinists had not taken power in the former Soviet Union and exerted such control over the communist movement.

- …according to the anarchists, if the communists had not sabotaged and destroyed their efforts at every turn.

- …according to the Stalinists, if after the Second World War the revisionists had not made nice-nice with the imperialist robber-barons.

And these speculations are only the broad outlines around which the different splits emerge in the “camp” of the oppressed. One might think it a paradox that these hyper-politicized divisions are taking place on a profoundly depoliticized field of action, but it only seems to be a paradox. Having only lived through one defeat, I cannot compare it to other periods. But everything I know of this camp makes me believe that there is a connection between defeat and turning in on oneself, and between surging forward and the dynamism that creates new possibilities to advance together, this in itself creating new possibilities.

There are various reasons for this profoundly depoliticized context. There is definitely the defeat that I have already mentioned. But even more than this there is out heritage,

“of a century of blood, of massacres and ruin (…) that we barely dare call ‘modernity’ and that obliged us to renounce all kinds of inevitability, if they were revolutionary. It is no less true that this pessimism (…) is itself anchored in a context. It is the reflection of that imperialism and hopelessness which is globalization, for no matter how much the virtually positive can show itself, the attention of the clearsighted is held by the extraordinary power of the negativity inherent in the system (…) For it is a system and this system, capitalism, has remained the same from the first up until its imperialist avatars which, through the rhythm of the many drastic changes that it has brought about and which have changed the way in which we see the world, have only confirmed its sickness, to the point of making it urgent (…) to change it. One does not need to look elsewhere to find something new. And it is radical. No matter how outdated, no matter how divided for seemingly circumstantial reasons, those who question this still have the same job to do. There are more and more signs that there will be, that there are at work convergences, whose programme may not be yet exist but whose final goal is undeniable.”23

Precisely because of this undeniable final goal, because of its renewed urgency, when we ask ourselves the “fatal” question – what is to be done? – we should stop demonizing power. This verb,24 its action, concerns our relationship to our own lives, what we have the power to do together. During 1999 a Manifesto of the Alternative Resistance Network was circulated fairly widely. Of libertarian inspiration, it correctly put the accent on Resisting Sadness.

“We are living in a period deeply marked by sadness which is not only tears but is far more so the sadness of powerlessness. Men and women of our period are living with the certainty that life is so complex that the only thing we can do, if we don’t want to make it even more complicated, is to submit to the discipline of economism, of self-interest and selfishness. Social and individual sadness convinces us that we are not really able to live a real life and from now on we submit to order and to the discipline of survival: the tyrant needs sadness because it isolates each of us in our little virtual and troubling world, just as those who are sad need the tyrant to justify their sadness.

“We believe that the first step against sadness (which is the form by which capitalism exists in our lives) is the creation, by various means, of concrete ties of solidarity. To break the isolation, to create these ties of solidarity is the beginning of a commitment, of militancy which is not ‘against’ but which is ‘for’ life and joy through the liberation of power.”

But a little later its libertarian inspiration made it state that resistance is the negation of a desire for power, for reasons both good and bad.

First of all the bad:

“One hundred and fifty years of revolutions and struggles have taught us that, contrary to the classic picture, centers of power are at the same time sites of weakness, even powerlessness. Power is busy managing things and is unable to change the social structure from the top down if the real connections at the base do not allow this. So strength is always separated from power. That is why we separate what is happening ‘on the top’ which is really management, from politics, in the good sense of the word, which is what is happening ‘on the bottom’.”

This distinction recycles the past years’ ubiquitous slogan of “civil society”. And it is in a sense the logical conclusion of this slogan that I heard when a representative of ATTAC25 sold the activity of his brand as a desire to “conquer society”, which would be a big change from past desires. When you think of all the dangers revolutionary militants have faced over the past 150 years just to get their ideas out there, this reversal of priorities makes me laugh – a little bitterly, but I laugh anyway it is so fucked.

This slogan carries with it another trap, even more dangerous: the central division would be between “civil society” and the State. What is this civil society? Who knows! Or more precisely, if we know a little bit of the concepts that serve the oppressed, we know that before Foucault, Gramsci called our attention to how such a concept disguises the class realities of our societies. In any case, in 1999 the MEDEF26 launched its “social refoundation”, in the vein of “civil society”.27 A coincidence in the history of slogans?

On the contrary, against this crippling reinterpretation of the history of the oppressed, the following statement from the same Manifesto deserves to be quoted:

“From now on, alternative resistance will be strong to the degree that it will abandon the trap of waiting, that is to say the classic political plan which always puts off the moment of liberation to ‘tomorrow’, to a little later…”

Quite true, “the path is made by walking” is a well known ‘law’ for all those who struggle. From a workplace strike to the guerilla, the fact that you struggle changes the situation. Resistance creates new relationships between people, new demands too but that is part of what is beautiful. And it is without a doubt something that will never be understood by those who live in the sadness of renunciation.

And so, to come back to your question, it is as a communist that I do not reduce the elaboration of possibilities to a conquest of power by the “proletariat”. Amongst other reasons because, while the two contradictions I mentioned earlier have developed to a planetary scale since the time of Marx, this has not simplified the identity of the famous proletariat. On the contrary. At the same time as the socialization of productive forces, tied to their development, has broadened the equally famous “historic mission.”28 This does not make it any easier to define the means that will allow the exploited class to act as a class for itself, a question that Marx and Bakunin already argued about almost two hundred years ago.

In short, if your question is trying to get me to clarify whether or not I believe in the transitory stage of the “dictatorship of the proletariat”… the answer is yes, and it is even one of the reasons why I call myself a communist. But if, on paper, this stage seems to me to be necessary, amongst other reasons because of all that we know of the power of the bourgeoisie to cause trouble to maintain its own dictatorship, don’t ask me what form this dictatorship will take, in order to work to abolish all classes, and from there to the withering away of the State as we have known it, as the tool of one class’s dictatorship over another. The Bolshevik model corresponded to an upsurge that happened almost a hundred years ago now. I am far too much a materialist to even want to propose it as an answer. But the model of the CNT/AIT in Catalonia in 1936, a “desertion” which led to the “vacuum” being filled by the Catalan bourgeoisie and the Stalinists, doesn’t have much of a chance of convincing me either… If I manage to draw the correct questions from these failures, I’ll be very happy…

Joëlle Aubron, Action Directe prisoner, July 2002

Other Texts About Action Directe

Resistance is a Duty! and other essays by comrades from Action Directe (available from LeftWingBooks.net)

Short Collective Biography of Action Directe Prisoners: Joëlle Aubron

Political Prisoners and the Question of Violence:: Action Directe

No Jail for Jean-Marc Rouillan! by Ron Augustin

Former Communist Guerilla Jean-Marc Rouillan Granted Restricted Freedom – the French State Appeals…

NOTES

1[The term “metropoles” refers to imperialist countries. One could also use the term “First World”. —Trans.]

2[In 1973 workers took over the bankrupt Lip watch factory in Besançon, France, and started running it for themselves. This experiment in self-management attracted a lot of attention from various left-wing groups. —Trans.]

3There are an abundance of examples, here are just two: obviously, the French Communist Party voting full powers to Guy Mollet to pacify Algeria, but also the attitude of the Cuban Communist Party while the guerilla was operative.

4[A reference to a popular French children’s’ cartoon, where the wicked buffoon Grand Vizier Iznogoud schemes to depose and replace the king. —Trans.]

5[Many revolutionaries and intellectuals saw the ruling class as carrying out preventive counter-revolution in response to the challenge of the 1960s movements. The term “preventive counter-revolution” was used by Herbert Marcuse in particular to describe repressive policies that try to prevent even the possibility of revolution. It should be noted that this is different from what radicals had termed “preventive counter-revolution” a few decades earlier, by which they meant fascism. —Trans.]

6[A quote from Karl Marx. —Trans.]

7[Translated means “Proletarian Left”. This was a theoretical magazine published by the group of the same name in Milan. This group grew out of the militant worker-student movement, and in turn it was from this group that the Red Brigades emerged. —Trans.]

8[The three continents being South America, Africa and Asia. More usually one would refer to the “Third World”, or perhaps the “global south”. —Trans.]

9[Queer French playwright Jean Genet made a distinction between “brutality”, which he saw as state-sponsored, and violence, which he saw as a legitimate weapon in the hands of the oppressed. When in 1977 he extended his distinction between bad brutality and good violence to a defense of the Red Army Faction in Germany, it created a furor against him across Europe. From then until his death in 1986, he remained isolated from white French society, his closest friends being Palestinians and his Moroccan lover. —Trans.]

10[ATTAC stands for Association for the Taxation of Financial Transactions for the Aid of Citizens. It is a network of groups against neo-liberalism and for ”democratic control of financial markets and their institutions”. Social-democratic and within the orbit of the newspaper le Monde Diplomatique, it is particularly active in France. —Trans.]

11At first, the COLP was just a name used to claim the attack on the Rovigo prison in January 1982, during which four prisoners, formerly from Prima Linea, were liberated. This attack was carried out by several small groups that remained from the armed movement in the Milan area following the decomposition of Prima Linea. This space around COLP, and then COLP itself, continued to work on prison issues and would eventually recreate a politico-military organizational structure. Inside the prisons, some would join the Red Brigades, others the Red Brigades split which intervened as the Wotta Sitta collective, others the libertarians, and still others would disasssociate themselves.

12[The RAF was in the habit of naming its commando groups after martyred revolutionaries. Khaled Aker was a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine–General Command who was killed on November 25, 1987 during an attack on an IDF base in the north of Israel. —Trans.]

13According to Alain Ménargues, a Radio-France reporter in Beirut from 1982 to 1995, the involvement of the Israeli armed forced in these massacres went far beyond passive complicity. The conclusions of the official Israeli inquiry, made puiblic in February 1983, went out of their way to note the personal responsibility of Sharon in carrying out the massacres. Now, in a to-be published book, Alain Ménargues provides evidence that an Insraeli commando unit was present. This unit was the first to enter the camps encircled by the army. With a list of 120 names, this unit carried out 63 summary executions against these Palestinian civilians, lawyers, doctors, teachers and nurses. It is only after this that a second and then a third wave of Lebanese killers entered.

14Meaning “real existing socialism”. Whatever the failures of this model in abolishing classes, and thus abolishing exploitative and oppressive relationships, its existence contributed to democratizing the imperialist stage, which is by its very nature a stage of decay and thus of reaction. It is no coincidence that the demise of this model led to further decay. The political crisis, which was illustrated by the recent elections amongst other things, is undeniably a part of this decay.

15[The “periphery” refers to colonies and neo-colonies; one might also say the “Third World”. —Trans.]

16[Besse was Director General of the state-owned Renault car company since January 1985. He was credited with Renault making a profit for the first time in years – a feat he managed by laying off 21,000 workers. On November 17th 1986, Action Directe’s Pierre Overney Commando (named after a Maoist militant killed by a Renault factory guard) rode up on a motorcycle as Besse emerged from his chauffeur-driven car – he was shot in the head and chest and died where he fell on the pavement. —Trans.]

17[On April 15th 1986, Action Directe’s Christos Kassimis Commando attacked Guy Brana, the vice-president of the CNPF (the French employers’ association) and the Director General of the arms branch of the Thomson multinational. —Trans.]

18[In September 1992, state-owned Credit Lyonnais was placed under administrative control by the French finance ministry as it became clear that the bank’s loan and investment portfolios contained massive unrealised losses, as a result of large loans and equity stakes in various businesses. While the French government safeguarded the savings of the banks’ eight million depositors, it meant bailing it out to the tune of billions of francs – over $17 billion US dollars worth. —Trans.]

19Of course, “liberation” and “emancipation” are synonyms. Nevertheless, by occasionally using the word “emancipation”, I am trying to go back to a major distinction. “All emancipation is a reduction of the human world and relationships to man himself. Political emancipation is the reduction of man, on the one hand, to a member of civil society […] and, on the other hand, to a citizen […] only when man has recognized and organized his ‘own powers’ as social powers, and, consequently, no longer separates social power from himself in the shape of political power, only then will human emancipation have been accomplished.” (Marx, On the Jewish Question) So liberation from that which oppresses works towards emancipation, understood as the opposite of alienation. This project cannot just be a search for paradise lost, human liberation and emancipation both make up a future in constant construction, the “from this day on”s leading to better possible tomorrows.

20In 1998 we wrote:

“As for current and future struggles, the undeniable historic break at the end of the 1980s is a crucial factor that one must take into account.

“That said it is equally important to point out that there is nothing extraordinary or cataclysmic to noting that a cycle of struggle has come to an end. Similar situations have already happened at least two or three times over the past century. Since the barricades at the Paris Commune, the revolutionary tradition on this continent has had to evolve, experiment, taste defeat and recognize it as such, and then set out once again ‘to storm the heavens’.

“It is worth dwelling on this evolution, made up of breaks and defeats ranging from the time of the old conspiratorial and insurrectionary tactics of the 19th century to the construction of large parties and unions, from the inability of these to oppose the butchery of the First World War to the Third International and the communist parties, from the latter’s post-war collaboration with the bourgeois system to the new revolutionary wave that broke with the mantras of modern revisionism.

“For today, what we want to retain from this can already be summarized by something obvious. Capitalism transforms itself by stages and, with these, cycles of struggle: revolutionary forms and means change as ‘the historic effect of the class struggle.’”

21[“Joelle Aubron: à propos de l’engagement.” 25-03-2004. —Trans.]

22Not everything, just almost, and it is important because the historical processes and political and social formations within which they reveal themselves make me think of what we are beginning to know about how the human brain works: matter, nothing but matter, but also chemistry from which the subjective participates, and so emotions in social, cultural and individual interactions.

23Georges Labica, introduction to “l’impérialisme stade suprême du capitalisme” c/ Le temps des cerises.

24[The French word for power is “pouvoir” – it is both a noun and a verb which means “to be able to”. Thus, in French the same word for “power” also means “ability”. —Trans.]

25I am targeting ATTAC because, in the journalistic construction that passes for public debate, this brand name has been given the job of opposition. But this discourse in which the past actions of those who wanted to change society are laughed at, are reduced to the story told by the victors, is widely propagated.

26[The MEDEF is the French Business Movemenet, an employers’ organization. —Trans.]

27Regarding this, see the paper by Paul Legneau Ymonet in « Revenir aux luttes » n°26/27 d’Agone.

28To give just one example of this: the fact that, if the productive forces are socialized, this socialization means that the collective appropriation of wealth takes into account the limits imposed by Ecology. Without which this wealth is not actually wealth, that is to say it buries the future and wastes the present.

Leave a Reply