Decades of torture, hundreds of men, weeks of starvation – and still we aren’t free! [SFBayView, Nube Brown]

[Reposted from SFBayView.com. Originally published July 16, 2021.]

Interview with Paul Redd and Ruben Jitu Williams by Editor Nube Brown

This is my interview with two incredible men who represent hundreds of others who have survived the torture of decades of solitary confinement and psychological abuse in California Department of Corrections and rehabilitation’s prisons, most notably, Pelican Bay State Prison. But no less important is these men are the Best of the Best, our loved ones. They are political prisoners, they are our heroes and brilliant, esteemed Elders. We will be centering and uplifting all their voices in this ongoing struggle for their release – we cannot, and will not, do this work without them.

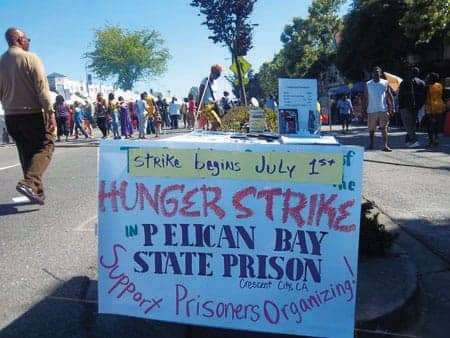

With me are Paul Redd and Ruben Jitu Williams. Both were integral in the first, second and third historic California Hunger Strikes, of which we are commemorating the 10th anniversary of the first Hunger Strike that started in July of 2011. Also out of those Hunger Strikes came the most important document and weapon against CDCr’s abusive tactics of the last 50 years, the Agreement to End Hostilities. I want to welcome these two men to the show, Paul Redd will you please introduce yourself.

PR: My name is Paul Redd; most people know me by PR. I spent most of my time in prison, close to 46 years, 30 something in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay. I was one of the 16 supporters, the representative body of the Hunger Strikes and to end the hostilities as well. On May 21, 2020, I was finally released from prison, Vacaville Prison, under 1170 (d)(1), (Penal Code § 1170(d)(1) CDCR Resentencing Recommendations (AB 1812). [Penal Code § 1170(d)(1) authorizes a court to recall a sentence and resentence a person to a lesser sentence. AB 1812 made changes that may help more people get CDCR recommendations for resentencing and also may help more people actually get resentenced. – ed.]

Nube: And we welcome you home, PR. We’re so glad that you are here with us today. And Ruben Jitu Williams, please introduce yourself.

Kubwa Jitu: My name is Ruben Williams and those that know me call me Kubwa Jitu. I too spent a total of 44 years in prison with 36 total in the SHU units; the last 26 years in Pelican Bay due to the activities that took place in the Hunger Strikes during the middle of the 2000s.

I was one of the individuals who was first released to the general population and about four years after that I was released into, back to Babylon. So, I’m here today and in discussion with a good friend of mine, Nube.

Nube: Welcome home, friend. That people like Kubwa Jitu and PR have spent decades in the torture of solitary confinement simply for their beliefs and political activities is something that we should not be allowing in any kind of civilized society. What they’re going to share with us needs to be looked at as a continued move forward and getting on board in this struggle to end any kind of solitary confinement, to get our people home, and in my view as an abolitionist, to abolish prisons altogether.

With that said, we have the 10th anniversary of the historic California Hunger Strikes coming up and I would love for the two of you to talk about what this means to you, but also dig back a bit during that time to share your thoughts on what was taking place back then beginning July 1, 2011.

Kubwa Jitu: My thoughts were on would many of us survive that Hunger Strike, because a lot of us had dedicated ourselves to the length of time that we were going to do. And looking at the history of Hunger Strikes, you notice and began to realize how much time we had before the system shut down and we began to learn what we were up against.

And yet most, not most, but quite a few of us were willing to take that challenge. So my thoughts going through my mind as we proceeded were how far could I push myself to continue to struggle if they split up and tried to fight back harder than we fought forward.

PR: And for me, PR, I knew in order to do this Hunger Strike that we were putting our lives on the line and we were going to make a big sacrifice. But we knew if we did this it had to have a serious impact on the system to where they would conceive and give in to our Five Core Demands.

At the time of the Hunger Strike, I didn’t consider my health problems that I was having, but I knew this was something that we had to do if we wanted to change the system that we knew was torturous, barbaric and everything else you can think of.

Nube: When you guys first started this, as you’re developing your communication strategies, ultimately getting 6,500 people to go on a hunger strike, how did you do that?

PR: Very simple – you relied on the facts. People got tired of continuing to be held in the SHU based on erroneous information, based on because you read certain books that had certain political views and newspapers etc. in your cell there. People said enough was enough.

They wanted a prison to be designed that would destroy prisoners mentally and physically.

So, when they got to the point where they wouldn’t accept that, people said, “Hey, man, I’m willing to do that Hunger Strike, and that was across the board of all races because people started realizing that loved ones of the outside world were dying up there. Those who had kids, their kids were growing up. They were confined up here in Crescent City in the boondocks so to speak; they couldn’t get visits. So people decided, hey, we need to do this Hunger Strike and we got a good, legit reason for doing it.

If we’re going to sit up here, we’re going to die anyway, so let’s die making a political stance because it seemed like we were never going to get out of prison.

Nube: Most people don’t find themselves in that place where they are willing to put their lives on the line. You guys had been in solitary confinement for decades by the time the first Hunger Strikes came around.

PR: Yes, but our politics were mature, so when we were able to talk, because of the structure of Pelican Bay, the sections you know, you don’t have to talk in a large audience. There are only eight cells per section, so it’s easy to communicate with anywhere from eight to 12 people in your section or over the tier.

Even those who may have just come into the hole, only been there for a year or two years, you’d be able to share your experience. And a lot of them were shocked when they heard our stories about how long we’ve been in the hole.

And when we explained and showed them what for, that even infuriated them. Because they realized, “Hey, I’m going to be like this too!” So, if there’s a cause of action that needs to be taken, then let me get on this fight, too.

Nube: Do you want to talk a bit about confidential information and about the “parole, snitch or die” environment that you were being placed under because that’s a form of torture as well, I think.

PR: You know, Nube, we were placed under that long before the Hunger Strikes were even organized, you know. Jitu said it and then I say it: We had been in the SHU long before that and we were being held in the SHU based on the fact that if we wanted to get out the SHU, we had to become a state agent and debrief.

All of that was military terms that CDC officials brought out of the military and tried to incorporate within the CDC environment, you know. You snitched or died to get out the hole, and that was the norm, you know.

They didn’t even have a policy, or a debriefing policy even though they lied and said they had one. But when they were challenged to produce the documents, then no documents existed to substantiate their claim.

They took a lot of what we were doing as a joke, you know. We went from a yearly review to a six-year review. It was constantly based on erroneous confidential information that kept us within the SHU.

The state government can determine what they want to do by how long they have before it’s overturned in the legal system.

Kubwa Jitu: Even up to the time when the debriefing process actually came to light, people didn’t really realize how many years they had been using that on us, literally. And I think Paul Redd is one of the individuals who initially tried to get them to put that word on record. Anytime they got to talking like that, they would shut off any recording they had, and they would tell you, “Well, here’s what you can do if you want to get out.” And we have people doing debrief, I mean years up until the day they made it legitimate to where they could actually say this term and have some legal foundation to stand on with it. But we have been facing that for what, maybe a dozen years, if not longer.

PR: You know everything the CDC was doing was underground policies.

Kubwa Jitu: Here’s where I think we kind of made a mistake; sometimes a lot of people, prisoners, say what they can and cannot do. In other words, the CDC will do something and somebody will holler out: “Man, they can’t do that. They can’t do that!” See, the thing is they can do anything they want!

What we have to concern ourselves with is, how long? This is what they contemplate. They figured that, OK, how long before these boys can get this to court? And how long (before they) can get a decision on it? And how long before he can get it overturned?

Their lawyers probably say four or five years, but four or five years’ worth of debriefing is extremely destructive. So, they had that time, and they held the courts up as long they could with some illegal activity that they later had to, out of their own mouth, had to admit to that they were wrong, so that’s what you had to face.

They said they were going to lock up the worst of the worst. Pelican Bay was designed to hold more than the 1,200 that it was for, but they were saying that they were going to put 500 of the most dangerous prisoners in Pelican Bay. Well, it turned out it was more than 500.

You’re faced with a section of the government here, the state government, that can determine what they want to do by how long they have before it’s overturned in the legal system. So that’s what we’re dealing with.

A lot of times we told ourselves, hey, they can’t do this, they can’t do that. All we were really asking them to do was adhere to the policies that you had already written in your Title 15 and your DOM (Department Operational Manual). They weren’t even adhering to the policies that were laid down by themselves!

We were fighting to get them to just, hey, adhere to your own stuff! We couldn’t get them to even do that.

PR: And they took a lot of this, what we were doing, as a joke, because like Jitu said, they were trying to see how far we would go. And as we showed that we were willing to go all the way to the end, they still took it as a joke because in the past you had other little hunger strikes that didn’t last so they figured that this is not going to last.

But, you know, CDC made the biggest mistake because they thought it was a joke. So, you know they kept threatening us with, “We’re going to take your TVs from you all” and a lot of us said: “Hey, come on and take it. You can get mine right now; just unplug it.”

So, they were like, “Why you wanna unplug your TV?” “Well, if I unplug my TV and I have nothing to look at, then I can think more about what I’m going to do about it against you, you know.” And they said, “Well, that’s what we thought,” so the union went to Sacramento and said, “No, leave these guys’ TVs in their cells.”

So, the next thing they thought they were going to come up with was this move to put us all in this Short Corridor. That was one of the brightest ideas I thought they ever came up with, you know, because they put you all in the Short Corridor. Now you’re able to communicate better.

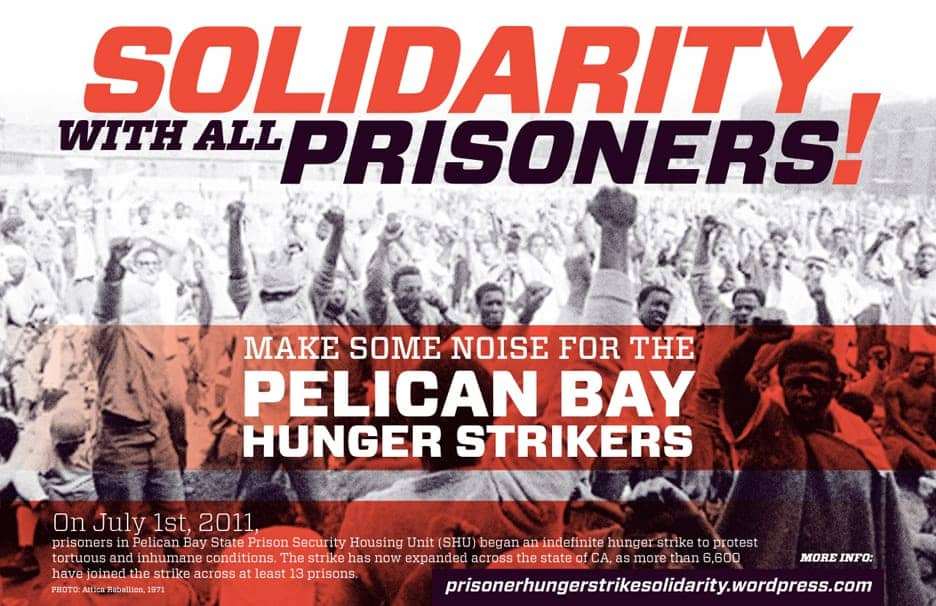

So that’s how we were successful in continuing to Hunger Strike to where we’d end up doing that third one and got 30,000 prisoners to support us, you know. And then they wanted to say: “Well, you guys had attorneys that came in and passed your messages around about the Hunger Strike.”

Attorneys had no involvement in us communicating about the Hunger Strike. Yeah, you put us all in the Short Corridor where we can talk on the wall, talk through the toilets, talk through the door, over the tier, but now you want to blame the attorneys – blame yourself for it.

Nube: Did either of you have an idea as to why you were brought to Pelican Bay State Prison, this supermax prison? Did you understand why it was being built and why you were put there when you first got there?

Kubwa Jitu: I knew what was being said, which wasn’t very much other than they have built a new place that was similar to something of a Level 5, and they were going to be holding the deadliest men in the state and blah blah blah. Other than that, I attributed to it all the same basic things attributed to the system to begin with.

You continue to build these prisons in these areas where the jobs, where the people are not financially that stable. It’s a small community and they always build them in these local areas, sort of build up these neighborhoods and these communities.

And these communities are all the same, you know. I’m not trying to make it a racial thing, but it’s always these white neighborhoods, these small communities way out somewhere and they use these prisons, you understand, to enhance the economic standards of these communities.

And also they began to move prisoners for the sake of destroying family lives and connections with the support groups and things like that, because as I stayed in Pelican Bay, I was dealing with things like people who I would write in Sweden and New Zealand and places like that, but getting envelopes, manila envelopes with newspaper clippings in them about some prison gang stuff that was taking place in another state and trying to attribute it to us in California.

Pelican Bay was designed to inflict torture from Day One.

They were telling these individuals that you shouldn’t be speaking with these people or shouldn’t be supporting them or contacting them and a lot of these people actually left. But there were a few who said: “I refuse to accept the words of somebody who refuses to put their own names at the end of a letter.” So, I was able to continue to communicate with some.

But their intentions were not blurry. I assumed they were just as the intentions were when they shot everybody up in these prisons around the state and beginning to build prisons for this particular type of prison setup, so yeah. As far as anything concrete, we heard what they said they were doing but we also knew historically what they were doing and how they were going about it.

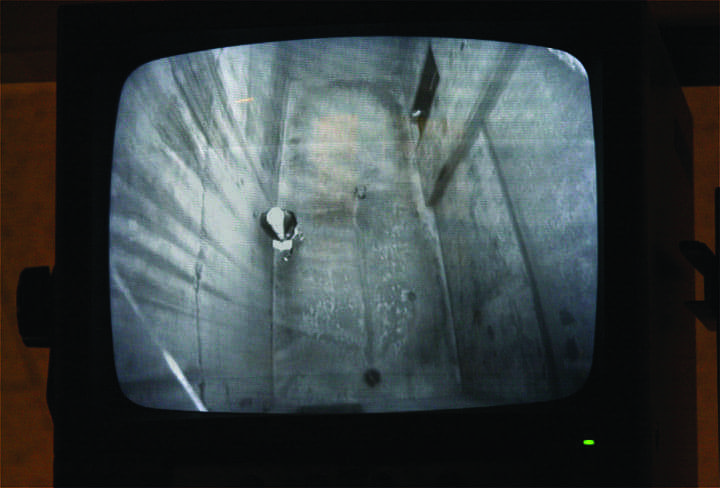

PR: Let me add to that, too, because it wasn’t until the late ‘90s that a private investigator named Tom Quinn, who worked for the attorney Catherine Campbell, wrote a confidential document that was quite a few pages. During his investigation he found out that there were secret meetings with officials who were told that they had a certain amount of money, and they used the funds to contact architects to come up with this design. They wanted a prison to be designed that would destroy prisoners mentally and physically.

They said they were going to lock up the worst of the worst. Pelican Bay was designed to hold more than the 1,200 that it was for, but they were saying that they were going to put 500 of the most dangerous prisoners in Pelican Bay. Well, it turned out it was more than 500, but they weren’t that dangerous because they were putting people up here who were in wheelchairs, who didn’t have legs and arms, as a scare tactic to scare them, they may have been filing complaints in some of these other prisons.

This report shed a whole light on why Pelican Bay was being designed, the politicians that were behind getting the money approved and how certain architects and certain politicians benefited from finding who was going to be able to get the contract for building this prison, which was going to be far worse than the one that was built in Arizona that was supposed to be used as a model.

Nube: It should be mentioned that this is where the people’s tax dollars are going because this is on our dime, torturing people. How soon in did you start making your complaints and trying to reach the outside. For instance, California Prisons Focus was the Pelican Bay Prison Express at that time. They started getting word from y’all inside fairly early. Can you go back to that time and talk a little bit about what you saw from the beginning and what you were doing about it.

PR: Yeah, when they first opened up and how Bato and Corey Weinstein and others got involved. You know, the first day people started arriving at Pelican Bay, the first prisoners, they immediately started sending out complaints to people and Bato and Corey Weinstein were very supportive and instrumental in putting together some people to help us investigate and collect our letters.

That’s how Pelican Bay Prison Express came to be and from there it turned into California Prison Focus. But they were the ones who were very committed, finding volunteers that would travel up there and pull us out of our cells and gather our complaints and hear our information. They would take that stuff back and put it on the drawing table and they would get at various attorneys to find out what they can do to help put this out there about this place.

There were a lot of complaints about Pelican Bay. I mean from the steel doors, they were faulty opening up because the electronics were faulty, the walls had cracks in them, they leaked, all kinds of stuff. And, you know, Pelican Bay was, like I said, designed to inflict torture from Day One.

Make no mistake; our fight is not over, because we still have friends and loved ones in these prisons that we have to get out.

And psychologically, when we used to hear about tsunami warnings in Crescent City, the guards would come by with a big old metal plate and slide in our door and put a lock on it. Because if there was going to be a big old flood like they had in 1965 in Crescent City, they were hoping that it would kill us all in these cells.

So they would save themselves, and even though it didn’t happen, just the psychological mind set of having somebody putting the double lock on your door and they’re running out of the building, that plays a lot on your psyche. That’s letting people know, man, these people don’t care about us being alive! They’re going to kill us, too! So, you know this is like mass genocide right here going down.

Nube: I wanted to go back to the building of this supermax prison, this Level 5 prison for apparently the worst of the worst. But now here you are talking about what they would do when there was a tsunami warning up there in Crescent City. Does that kindle any kind of reminiscence of what you two are seeing now with COVID-19 and how they’re handling it in the prisons?

PR: This COVID-19 took it to a whole other level, you know, because it killed millions of people across the country, and the world. But when it came to the prisons, I mean it goes all the way back to the Hong Kong flu and all these other diseases that came out that hit prisoners hard, you know.

You have to keep in mind the medical quality of care inside the prisons has always been shabby. You know, it’s all about money. So when it came to COVID-19 starting to spread in prison, even before it spread, the guards were complaining!

“Man, why aren’t they checking us? Why aren’t they doing this temperature check? Or why are they doing the temperature check when they’re not following up on all this here?”

So, you had a lot of guards that were complaining about it. But CDC didn’t care about what they were saying. Even the union was trying to get them to do things, and if they didn’t care anything about their own, they really didn’t care anything about a prisoner.

It was impossible to even have that 6-feet social distance inside of prison, the way these prisons are built, these dayrooms are built. So, when you go back and look at the way these prisons were built, the way these new prisons were built, it was all about genocide. That’s the bottom line, genocide, you know, mass murder. Just keep it real: mass murder.

Make no mistake; our fight is not over, because we still have friends and loved ones in these prisons that we have to get out.

Nube: I want to thank you for using the term genocide. I agree that’s the correct term for what’s taking place. I wanted to ask do you also consider the building of this prison, picking and choosing who’s going to go inside and calling y’all the worst of the worst to be like another form of COINTELPRO?

PR: Let me say this: One of my comrades said: “Brother, they call us the worst of the worst, but you know, in reality we are the Best of the Best because we did a lot of stuff to be broken and here we are now out here in Babylon, not behind the walls.”

And yet for years we were called the worst of the worst, but now we walk out here in the free world to continue to do the positive work that we’re doing to bring others home. So we weren’t the worst of the worst; we were the Best of the Best and we showed we were the Best of the Best because we survived it.

What they were trying to inflict on us were the worst conditions possible, and in some cases they were successful, but at the end of the day those of us who were strong are still standing and those who are still behind the wall are still standing, fighting to the end.

Nube: I would love to name some of those men, those heroes, those political prisoners, those survivors who are still standing. Can we name some of them?

PR: We can name them all who are still being held in Tracy, in Folsom, in Soledad, in Tehachapi, in New Folsom and Old Folsom, in Corcoran, in Kern Valley, in Salinas – we all know who they are. I mean we can name them all and still not be done.

The thing is are we willing and prepared to get them up outta there, because once we get them all up outta there then we can put their names on this list, the survivors of the hell hole that’s still being inflicted upon them.

Nube: Can we talk about the Five Core Demands? You all were not asking for anything outrageous.

PR: I just want to put it like this because we’re dealing with the 10th anniversary of the strike. So again, we were successful in pushing CDC to change some of the policies confining us in these SHUs for decades and decades.

One of the main things that gave life to it is that we were not going to accept continuing to be punished, especially through what you call group punishment. We said, hey, if you’re going to punish us, punish us individuals with something we’ve done, not as a group because we know that you’re sitting up here abusing it and acting arbitrarily with your power to inflict this punishment.

[The first core demand: “Individual Accountability: This is in response to PBSP’s application of “group punishment” as a means to address individual inmates’ rule violations. This includes the administration’s abusive, pretextual use of “safety and concern” to justify what are unnecessary punitive acts. This policy has been applied in the context of justifying indefinite SHU status and progressively restricting our programming and privileges.”]They are still being retaliated against because they participated in the Hunger Strikes. They didn’t violate any CDC rules.

And that includes the parole board, you know. So again, to sit up here and start talking about the Five Core Demands means we were successful in exposing the fraud that CDC was doing. Now 10 years later, we still have loved ones we have been on yards with of all races! And they are still behind those walls even though most of them have been released into the general population.

They are still being retaliated against because they participated in the Hunger Strikes. They didn’t violate any CDC rules. How are you going to tell a grown man that he’s got to accept your food that you bring to his door? Then you’re going to write him up because he refused to eat your state food?

Even the courts agreed in one case: Gomez (Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D. Cal. 1995)), a prisoner who participated in the Hunger Strikes, questioned his disciplinary report [Form 115], contending that this was no gang activity and does not cause a threat to the institutional security, so the courts ordered his 115 expunged; but yet all the rest of us who got write-ups for that, CDC didn’t want to go back and remove our 115s even though they knew that we violated no rules.

They just did what they wanted to do, and we decided enough was enough. And we were able to talk to other people that lived around us who concurred with that, you know, and they seemed to mark their own selves being inflicted upon and that united us together. Like George says: “Settle your quarrels, come together.”

So, we always knew that the power of unity speaks loud, and we showed it with the 30,000 that participated. And we showed that made CDCr take heed because we had people around the country and other countries that supported us in joining the Hunger Strikes as well. And that put the spotlight on the United States, as well as CDCr.

Nube: In light of Juneteenth just being signed in as a national holiday – knowing that we still aren’t free and that legal slavery is taking place within our prisons as codified by the 13th Amendment exception clause; and this victory also came about due to the creation of the most important document of the last 50 years, the Agreement to End Hostilities, what would either of you want most from the focus on this 10th anniversary?

PR: What I would like to see is the people out here in the community to unite with us and let us put more pressure on these politicians and substantially change these barbaric laws that have unjustly criminalized the incarcerated.

You have people who had been tried as adults but yet they were juveniles. And then you have laws that came out, you know 20, 30 years later to say, hey, you can’t convict a juvenile as an adult because his mind is not developed; it’s not matured.

And you have the United States Supreme Court hampering that. The Supreme Court is not sending the directive down into the lower courts to say, hey, go back to all the people that were convicted when they were juveniles and hold new hearings for them and then release them.

They’re not doing that, so we need to put pressure on these politicians for what we want to see changed and not just be asking about it but let them know we’re serious about changing; and if they’re not for it, we get them out of office.

Nube: Indeed, Kubwa Jitu?

Kubwa Jitu: Oh hey, me personally, as I said, Nube, remember in the California Prison Focus meetings that California Prison Focus helped bring back the community to the support of prisoners and I think in order for any success to continue, we must continue to have the community involved.

And in some cases more involved hands-on activity wise. I think that history has shown that when the people stick together, such as we did along the way, success is there. Success is to be had.

But if we allow ourselves to fall back into those pitfalls where we allow these outside forces to separate us and our thought patterns and our willingness to do things, then we’ll find ourselves right back to where we were before we began in this struggle. Because they’re going to fight us every step of the way and we know that, we accept that and we also accept the fight.

But we also know that we still need the community to stick with us. The community has seen what the truths were, they’ve seen what the lies were, they’ve seen the injustice that is taking place within these warehouses in which they place individuals based upon the assumption that you might be somebody, you might do something, hell, you might be thinking. So yeah, that’s where I am with it, Nube.

Nube: I’d like to have you guys talk about the Agreement to End Hostilities. I think it really is the most important document that was created in the last 50 years. This document seems to speak so powerfully to what we need to do in terms of our own social political education, organizing and activism in solidarity, all of which you both spoke so eloquently about.

Paul, your name is on that document, but I know that others were supporters and put in the energy whose names are not on that document. I would love for both of you to just share something about the Agreement to End Hostilities.

Kubwa Jitu: I’ll let Paul do that since he was part of the process that set it in motion!

PR: I’m just going to put it in a nutshell. Us behind the walls who were putting together this Hunger Strike realized that CDC officials, IGI, prison guards were going to try to sabotage this Hunger Strike. We knew they were going to play games, divide and conquer, create certain little things to have people not support the Hunger Strike.

So, we knew we had to put this document together to educate people. Let us stop bickering, fighting amongst ourselves. Whatever dispute we have, let us come together as men and discuss it and resolve it, because this Hunger Strike was bigger than all of us.

From the Hunger Strike and 30,000 prisoners coming together to support that cause, now you’re looking at some of these individuals on the street of different races, different groups coming together to put this food drive together to feed the homeless.

This Hunger Strike was to bring an end to this injustice that was being inflicted upon us. So we knew we had to get this word out, this document out, to the wives, the county jails and into every place that we can get it to so people can see and realize: Let us now come together. This is the time to make the changes.

And that was one of the most important things that we were able to do, and it worked because after I had gotten out of the SHU, I ran across a lot of individuals from different races commending us for coming together with that Agreement to End Hostilities because it helped to stop a lot of the internal fighting, as well as the fighting amongst other races.

And once that happened, the prison officials realized they lost their grip. It was a new day.

Nube: Beautiful. Going back to the Best of the Best, would either of you like to talk about the incredible food distribution that you all did for the community a few weeks ago? Do you want to talk about and uplift that beautiful coming together from one of the Brothers, Richard Johnson, who came home just recently?

Kubwa Jitu: You know that was a beautiful thing for me because it made me kind of realize, no, realize is the wrong way, it made me kinda float around in my mind how it must’ve been those years upon years ago during the matriarchal society when our people were sharing food in that same manner, you know. We know that those types of societies are long past, but you can read.

When I stood out there and looked up and down that row, I looked up and thought about people coming together to meet the people on every level of life that we knew reality to be and that was we all got a chance to eat; nobody was left behind; it was food for everybody and it kind of made me think back to how it was before it became watered down and tampered with and faced with destruction, you know.

Nube: Wow, it’s almost like this is the ultimate form of not being broken by being able to tap into your roots, being able to dig deep, to reach far and come from your roots as African peoples, New African peoples and do work that is natural to your cultural and ancestral roots after spending too many torturous years buried in a 9×6 concrete box isolated away from your people.

PR: You know, with me this food organizing that we did on June 5th reminds me of the teachers that we had when we look at this Hunger Strike – 30,000 prisoners coming together to support that cause. Now you’re looking at some of these individuals on the street of different races, different groups coming together to put this food drive together to feed the homeless, those who are in need of it during this COVID-19.

And some of the people who were instrumental in passing out the food were some of the people who came out of prison. So again, you don’t have the worst of the worst, but the Best of the Best.

We’re all Paul Redd. When anybody who’s signing their name on behalf of the people, that name becomes the name of all the people.

We were able to come out here and align with other people that were out here and man, it was the biggest food give-out that I’ve ever seen, and the biggest I’ve ever seen was on the TV during the news broadcast.

But to actually be a part of that and be in West Oakland where you were raised – DeFremery Park that (is proposed to be) named after Bobby Hutton, you know, that was symbolic. And my hat goes off to Richard Johnson and all the other people who supported and were behind this and the list went on, you know. And it was just, man, I mean I’m still talking about it and trying to figure out when we’re going do this next one and when we’re going to make it bigger than this one.

Nube: Fantastic. Kubwa Jitu, did you have any last thoughts on this 10th anniversary or any other last thoughts?

Kubwa Jitu: Well, my last thought would be in regard to the commemoration because you know we commemorate quite a few things and commemorate quite a few people. And as Paul said earlier, when you start to name names, I’m absolutely certain somewhere along the line we would forget one or two. And so I’d like to look at it that when Paul Redd signs Paul Redd, we’re all Paul Redd. When anybody who’s signing their name on behalf of the people, that name becomes the name of all the people – and that’s how I look at it.

And like I said, the commemoration of any successful struggle should be one to enjoy and to endure throughout the day. There will be many more, you know. Some we may witness, some we may not, but there will be many more.

Nube: All right, thank you both for that! This has been a beautiful conversation and I know that we will continue to have more, especially as we take this moment in time, this golden opportunity to further expose what is truly taking place, what has taken place and educate the people. PR and Kubwa Jitu, you two are amongst the Best of the Best.

I want to thank you both for being in conversation with me. I don’t know if you know, Kubwa Jitu, but I am now the editor of the San Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper.

Kubwa Jitu: No, I did not know, and it couldn’t happen to a better person. Congratulations! And you know that’s from the heart, too; you know that’s real.

Nube: Thank you, thank you. I’m mentioning that only because I now straddle both places. You know I’m still doing the work with Liberate the Caged Voices and I have a column now in the San Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper. So, it’s really such an honor to be able to be in this place and be able to bring your voices forward in this way to the community locally, but also nationally and hopefully continue to inspire new activists out here and on both sides of the wall and together get our people home.

I appreciate you two so much, thank you. I’m going to say have a beautiful rest of your afternoon, I send you a clenched fist of love and solidarity, of course, and may we always act in shared humanity and uplift one another.

PR: That’s what it’s about. Push it forward, push it forward.

Kubwa Jitu: Each one, teach one.

Send our brothers some love and light: Jitu Williams can be reached at jitu44yrs@gmail.com to further understand the effects of spending 44 years of one’s life in the belly of the beast. To reach Paul Redd, contact Bay View Editor Nube Brown at nube@sfbayview.com or 415-671-0789.

Leave a Reply